More students in India will be able to step inside a classroom for the first time in nearly 18 months Wednesday, as authorities gave the green light to partially reopen more schools despite apprehension from some parents and signs that infections are picking up again.

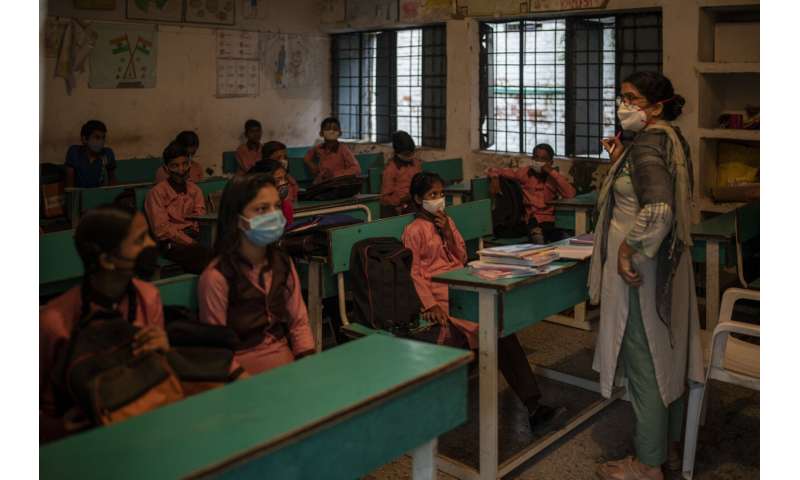

Schools and colleges in at least six more states are reopening in a gradual manner with health measures in place throughout September. In New Delhi, all staff must be vaccinated and class sizes will be capped at 50% with staggered seating and sanitized desks.

In the capital only students in grades nine through 12 will be allowed to attend at first, though it is not compulsory. Some parents say they will be holding their children back, including Nalini Chauhan, who lost her husband to the coronavirus last year.

“That trauma is there for us and that is what stops me from going out. We don’t go to malls. We don’t go shopping. So why schools now?” she said.

Life has been slowly returning to normal in India after the trauma of a ferocious coronavirus surge earlier this year ground life in the country to a halt, sickened tens of millions, and left hundreds of thousands dead. A number of states returned last month to in person learning for some age groups.

Daily new infections have fallen sharply since their peak of more than 400,000 in May. But on Saturday, India recorded 46,000 new cases, the highest in nearly two months.

The uptick has raised questions over reopening schools, with some warning against it. Others say the virus risk to children remains low and opening schools is urgent for poorer students who lack access to the internet, making online learning nearly impossible.

“The simple answer is there is never a right time to do anything during a pandemic,” said Jacob John, professor of community medicine at Christian Medical College, Vellore. “There is a risk, but life has to go on—and you can’t go on without schools.”

Online education remains a privilege in India, where only one in four children have access to the internet and digital devices, according to UNICEF. The virtual classroom has deepened existing inequities, marking the haves from the have-nots, said Shavati Sharma Kukreja of Central Square Foundation, an education non-profit.

“While kids with access to smartphones and laptops have continued their learning with minimal disruption, those less privileged have effectively lost over a year of education,” she said.

A study released in January from Azim Premji University surveying over 16,000 children found staggering levels of learning loss. Researchers found 92% of children had lost crucial language skills, like being able to describe a picture or write simple sentences. Similarly, 82% of children surveyed lacked basic math skills they had learned the previous year.

For Giesem Raman, a teacher in a remote village in northeastern Manipur state, such data matches what he has seen in person. The small primary school where he works closed its doors for the second time in April. With no facilities for online lessons, classes haven’t taken place in any form.

When his students were briefly allowed back into school earlier this year, he said many had forgotten nearly everything they had learned.

“It saddens me to see how the future of these kids may have been destroyed,” he said.

In Uttar Pradesh state, where school reopens for first to fifth graders on Wednesday after older students were allowed last month, 6-year-old Kartik Sharma was excited to wear his new school uniform. His father, Prakash Sharma, said he was “satisfied” with the virus protocols the school has in place.

“The arrangements the school has made are top class,” he said.

Not all are as confident. Toshi Kishore Srivastava said she would wait before sending her son back to first grade.

Source: Read Full Article