When cancer metastasizes and spreads throughout the body, it can severely change the prognosis of the disease. It is estimated that metastasis is responsible for 90 percent of cancer deaths.

University of Chicago Medicine investigators have found a new way to slow the metastasis of colon cancer: by treating it with a small molecule that essentially locks up cancer cells’ ability to change shape and move throughout the body.

In a mouse model, the molecule cut the rate of cancer metastasis in half. Though more research is needed, the result could ultimately become a new therapy that, when combined with radiation and chemotherapy, could help provide better outcomes for several types of cancer.

“It’s a very promising approach,” said Ronald Rock, Ph.D., Associate Professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at the University of Chicago and co-author of the paper. “It appears to be broadly applicable. If you can improve outcomes by 5 or 10 percent, that will help a lot of people.”

The results are published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Rock co-authored the paper with Ralph Weichselbaum, MD, Daniel K. Ludwig Distinguished Service Professor of Radiation and Cellular Oncology and Chair of the Department of Radiation and Cellular Oncology at UChicago.

“It’s a new area of cancer treatment, and we’re really excited to see how far this can go,” Weichselbaum said.

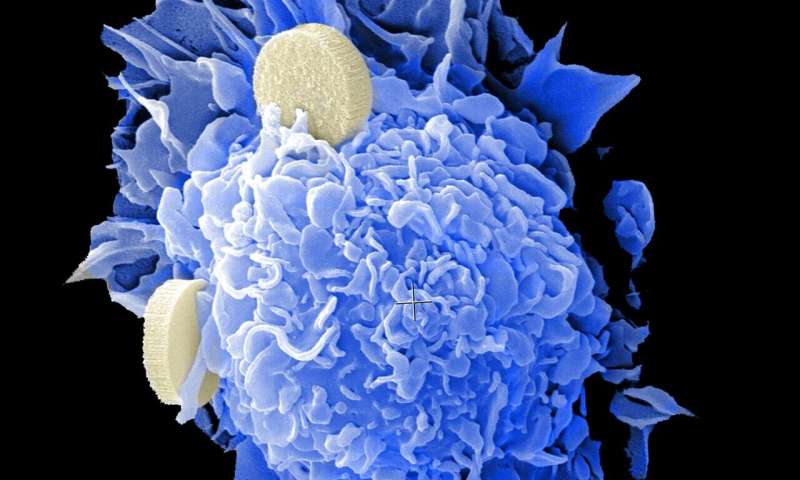

For cancer cells to disseminate from a tumor throughout the body, they must remodel their structure and increase their deformability to essentially crawl through tissue and worm their way into the bloodstream.

But Weichselbaum, whose research focuses on metastasis, wanted to find a way to stop that process in its tracks. He and Rock began to study a small molecule called 4-hydroxyacetophenone (4-HAP), which activates a protein in the cancer cell called nonmuscle myosin-2C (NM2C). That protein is one of the machines that allows the cell to deform and travel. When activated, it becomes locked in place, ensuring that the cancer cell cannot travel.

The investigators studied this process at both the molecular level and using human colon cancer tumors in a mouse model, and found that it significantly limited the cancer’s ability to metastasize to other parts of the body, while leaving healthy cells alone. The rate of metastasis was cut in half, compared to non-treated colon cancer.

The team envisions using this molecule in tandem with chemotherapy and radiation to create a more effective cancer-killing treatment.

“Using this molecule means there are fewer cancer cells traveling in the body, so they would be easier to kill with radiation or chemotherapy,” Weichselbaum said. “It we can decrease the spread, we have a better chance of curing the patient.”

The molecule could be an improvement over other treatments for metastasis, like kinase inhibitors, which are the basis of many chemotherapies. Those treatments work by targeting the enzymes that allow cancer to proliferate, but many times, cancer cells just find a workaround.

“With our approach, we’re essentially pouring sand right into the machine,” Rock said. “There’s no way for the cell to get around it. The engine is not going to run.”

Though the experiment was conducted on colon cancer, these preliminary results show that the molecule could work on several types of cancer that metastasize. Next the team hopes to find other molecules that could also inhibit NM2C to create a multi-layer approach for hindering metastasis. That’s important for up-and-coming physicians like Darren Bryan, MD, a former UChicago Medicine surgery resident and first author on the paper.

Source: Read Full Article