Several years ago, while I was doing final sweeps through a book I’d just written, I began to notice that my eyes were having a hard time speeding through the manuscript. That didn’t really bother me, because the protagonist, a big-wave surfer named Greg Long, had such bad eyesight that he had trouble spotting giant waves on the horizon, and my situation wasn’t anywhere near that. Still, this was problematic. I’d always been a speedy reader who didn’t sweat small fonts, and I’d never needed glasses for navigating tricky terrain while mountain biking, surfing, or skateboarding. Yet one night, there I was, barely into my 50s, highlighting typos with a pair of 1.5x readers draped across my nose. I wondered, Is this my future?

What was happening to me—and will eventually happen to you, your younger brother, and Tom Brady—is called presbyopia. You don’t notice this condition initially, but presbyopia can start as early as age 30. Every five years after that, you’ll lose the ability to focus on one more line on the eye doctor’s letter chart. By 40, most of us will start noticing it, squinting here, moving the iPhone a little farther away from the face there, whether or not you’ve ever worn glasses. And right around the big 5-0, nearly all of us are afflicted.

Because I’ve never been hindered by a need to keep track of eyeglasses but I need to do a lot of reading for work, I dreamed of some outside-the-box solution to improve my eyesight rather than glasses or contact lenses. The first thing I learned is that presbyopia is correctable with surgery—monovision Lasik, corneal implants, or lens-replacement surgery—but I’m leery of having laser beams or scalpels etch my corneas.

Then one night while Googling the condition, I was led to an app called Glasses-Off. It promises to help you read type 50 percent smaller than you can right now and perhaps improve your reading speed significantly. There was even research indicating that the eye exercises it asked you to do could help you respond a few milliseconds faster to, say, a baseball flying at you, by improving a brain activity called visual processing.

What This App Requires You to Do

GlassesOff asks you to spend less than 15 minutes three times a week reacting by touch screen to tiny, blurry striped balls called Gabor patches as they flash across a featureless gray background. Early on, the patches are larger, slower, and better defined. As you progress, they appear and disappear more rapidly, eventually becoming mere ghostly dots that can be incredibly hard to see. And that’s the point.

The very idea that this app might be effective in improving my eyesight seemed suspicious, since nobody I knew who needed to wear reading glasses was talking about this $10-a-month app. And it seems even more far-fetched when you take biology into account. Presbyopia occurs when your eye’s flexible lens—which is the shape and size of a soft Skittle—isn’t so flexible anymore. To focus up close, you contract the muscles that hold the lens in place. As you age, that Skittle hardens. You compensate by squinting, but in time, not even that helps.

Presbyopia is a game of dominoes, and your lens is only the first to fall. The next is neurological: That blurring of everything you should be seeing hampers your ability to discern contrast and interferes with how smoothly your neurons stream visual data to your brain. Basically, presbyopia chokes visual processing, slowing down reading and even response times.

The History Behind These Eye Exercises

About 12 years ago, a neuroscientist named Uri Polat, Ph.D., director of the Visual and Clinical Neuroscience Lab at Bar-Ilan University in Tel Aviv, Israel, wondered if he could get around that by harnessing the science of neuroplasticity—essentially training your brain to process what it is seeing faster and more clearly. This might have the benefit of enhancing not only near vision but also reaction times. Low image quality puts a load on your visual-processing abilities “and probably creates a bottleneck for the cognitive levels of the brain,” says Polat, now chief scientific officer of the company that developed GlassesOff.

In a recently published study, Polat’s app was tested on guys whose visual acuity really matters: Israeli fighter pilots. Their visual clarity improved by an average of 35 percent, and their responsiveness to visual cues went up 25 percent—crucial when trying to recognize a camouflaged enemy plane streaking toward you at 700 miles an hour. Research on American baseball players showed similar results. A study by Polat in Nature Scientific Reports found that users were able to speed through lines in the smallest font they could discern on a reading chart 25 words per minute faster than they could when they started using the app. People with the most advanced presbyopia had the greatest gains, raising reading speed from about 47 to 85 or so words a minute.

Those figures were impressive enough for me to be intrigued. GlassesOff is not the only vision-improvement app on the market, but it’s the only one with any serious scientific study. (One competitor, Ultimeyes, was fined by the FTC for claiming that it could improve vision without having published data to back it up.) But to believe it, I had to test it myself.

The Experiment

Since I wanted to know whether I was just imagining things or my eyes had really improved, I visited Hugh Wright, M.D., a lead ophthalmologist with the Roper St. Francis Hospital System in South Carolina, where I live. He measured both my distance and near vision at around 20/25. My near vision is better than average—on a par with that of a person in his late 30s—but now that I’m 52, my presbyopia is likely on an accelerating path.

I devoted the recommended ten minutes to GlassesOff almost daily and used it for eight weeks, the minimum required time to see results. The app is at first novel and challenging, but the repetition becomes monotonous. A month in, though, I was squinting less. Headlights and road signs seemed sharper. I stayed with it, and three months after my first visit to Dr. Wright, my chart vision remained pretty much the same, but I was now reading without glasses again. What was tough for me to decipher before—the five-point fine print on a Dale’s Pale Ale can—was clear to me now.

It could be because, according to the app, my contrast sensitivity had increased by 51 percent and what Polat terms my “brain processing speed”—the rate at which I’m able to recognize a Gabor patch onscreen—shot up by 80 percent.

Dr. Wright wasn’t ready to fully endorse GlassesOff, saying the evidence is too limited to wholly support enhancing neuroplasticity to reverse presbyopia. But he didn’t dismiss it, either. “Standard vision screening in clinics typically doesn’t assess for contrast sensitivity or visual response times, which GlassesOff does,” he said. “If patients see improvement in these areas, then I see it as a plus.” Those two measures are critical when dropping into a steep wave or skating vert, and that may matter to me more than what a static eye chart says. “Neuroplasticity is a very real thing,” Dr. Wright added. Making more connections is good for your brain performance, regardless of what it might do for your eyes. But, doctor that he is, he warned that the app shouldn’t be used in place of getting your eyes checked regularly or wearing glasses if you need them.

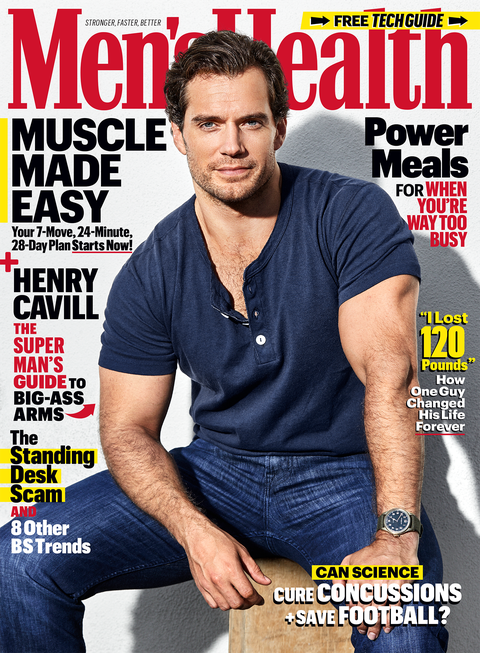

Subscribe to Men’s Health

SHOP NOW

Ultimately, both men agreed that nothing will completely halt presbyopia. Polat, of course, suggested that sticking with the program’s maintenance regime (12 minutes a day once every two weeks) would help prevent my vision from declining significantly.

Even if it’s not perfect, I’m still a writer and need to continue reading. And despite a skateboarding-related broken shoulder I wrote about for this magazine, sharing runs at the skate park with my ten-year-old son is about as rewarding as life gets. I need all the help I can find, so I’m going to stay with the app.

Source: Read Full Article