Understanding the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying brain plasticity (how the brain can learn, develop and reorganize itself) is crucial for explaining many illnesses and conditions. Neurocientists from the University of Göttingen and University Medical Center Göttingen (UMG) have now managed to repeatedly image synapses, the tiny contact sites between neurons, in awake adult mice. They are the first to discover that adult neurons in the primary visual cortex with an increased number of ‘silent synapses’ (ie newly formed synapses that are inactivated), lacking a certain protein (PSD-95), display structural changes that were previously only reported in young mice. This research by the Collaborative Research Centre CRC889 was published in PNAS.

It is well known that during early brain development, there are critical periods during which the brain is particularly plastic and individual experiences can trigger reorganization and adaptation in neuronal circuits. In developing brains, silent synapses are common and they help to functionally optimize the connections between principal neurons. The research teams of Professor Siegrid Löwel (University of Göttingen) and Professor Oliver Schlüter (UMG) had already discovered that the maturation of silent synapses requires postsynaptic density protein-95 (PSD-95) and closes early critical periods. However, the specific processes that govern whether synaptic connections are kept or removed depending on experience were largely unknown.

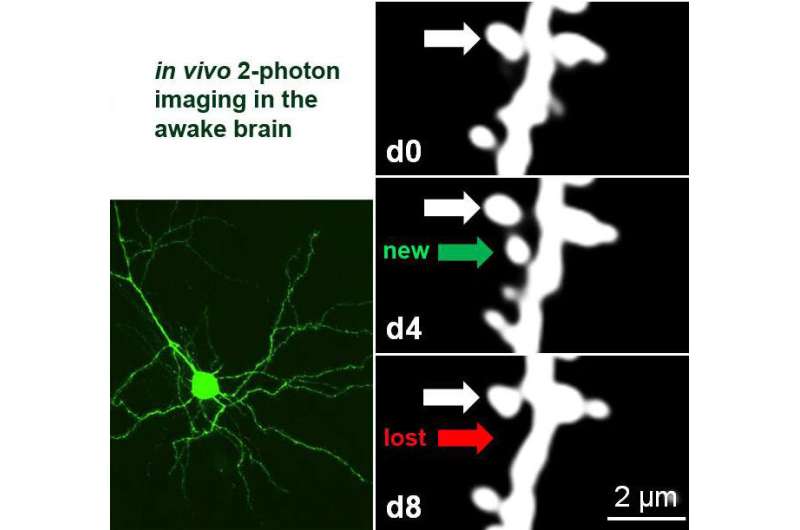

To investigate this, the researchers imaged neurons from the mouse visual cortex with a two-photon microscope while the animal was awake before and after a particular visual experience. As first author Rashad Yusifov from the University of Göttingen explains, “Previous studies have generally used anesthetized mice but we now know that anesthesia itself can influence neuronal plasticity, which is why we did the current study in awake animals.” Yusifov goes on to say, “This challenging technique, which entails repeatedly locating and imaging very tiny structures—around one-thousandth of a millimeter—known as dendritic spines, can only be carried out in a few laboratories in the world”.

Source: Read Full Article