It’s essential that today’s politicians and decision makers recognize the many and severe risks that the climate crisis poses not just for our physical health, but also for our mental well-being. Unfortunately, at least in the UK, politicians so far have demonstrated little awareness of the direct and indirect links between climate and mental health. That’s the worrying conclusion of a recent study in Frontiers in Public Health, where researchers mined the public records of all debates in the UK’s House of Commons and House of Lords between 1995 and 2020.

The authors found that on the few occasions that speakers showed any awareness of these links, the focus of their speeches was always on the association between flooding and anxiety. But no-one mentioned any of the other proven mental health impacts of climate change. For example, higher temperatures are associated with higher suicide rates and more hospitalizations for mental disorders.

Likewise, extreme weather events such as wildfires, floods, droughts, and severe storms are associated with worse mental health in affected populations. And research has shown that so-called negative ‘eco-emotions’—that is, worries about the effect the climate crisis will have on society and the environment—are widespread in many countries today.

The study’s lead author Lucy Pirkle, a former student at the Department of Brain Sciences at Imperial College London, here discusses the findings and puts them into perspective:

It is becoming harder and harder to ignore the impacts of climate change. The frequency and severity of extreme weather events and other, more insidious changes that alter our environment are on the rise. Recently, over one-third of Pakistan was under water due to severe flooding, likely made worse by the warming climate. The devastating effects of climate change are also impacting the UK. This summer has been the hottest on record, with early reports suggesting the record-breaking heatwave in July 2022 was made “at least 10 times more likely” by human-caused climate change. This extreme heat without sufficient rainfall has led to droughts being declared across the country.

It is now becoming clear that without rapid and effective policy action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, these disastrous events will continue to get worse, with a devastating impact on people’s lives and livelihoods. Therefore, alongside these mitigating policies, we must also adapt and work quickly to build resilience within communities to protect people from further climate-related events. However, to ensure these policies go far enough to protect population health, those who have the power to design and set these policies must fully understand the challenge we are facing.

Hidden mental impact of heatwaves

It is widely reported that climate-related events lead to significant mortality and morbidity. Extreme temperatures alone are estimated to account for 5m excess deaths a year globally already. Although important, physical injury and death tolls only tell part of the story. There is mounting evidence that climate change, through direct or vicarious experience, is also affecting people’s mental health.

Direct mental health impacts of climate-related flooding were, for example, reported in the Public Health England commissioned English National Study of Flooding and Health. This stated that the 2013-14 UK floods significantly increased probable depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in affected individuals, even two years after the floods.

Suicide rates have also been shown to increase during direct experience of heatwaves. One report found a 49.6% increase in suicides during the 1995 heatwaves across England and Wales, with relative risk increasing with every degree increase in ambient temperature. However, these effects must be explored further as no effect was seen in the 2003 heatwave.

Climate change has also been shown to indirectly impact mental health and emotional well-being. Feelings of distress and anxiety are linked to increased awareness of the unmitigated climate crisis and the effect it will have on the health of our planet and our society.

Negative eco-emotions have been found to predict both insomnia and lower self-rated mental health, highlighting the potential implications of climate-related distress for mental health and indicating this could be a considerable burden as climate change worsens in the UK and globally. Certain groups, such as children and young people are thought to be at increased risk of eco-anxiety and the implications for their longer term mental health and well-being remain a key target for further research.

The mental health consequences of climate change have been described as hidden costs which are not currently considered within policy and planning. Research, both in the UK and globally, has started to uncover patterns and suggest opportunities to create win-wins for climate and public health. To achieve those wins, decisive and joined-up action is required.

For example, as recently suggested by Lawrence et al, there are synergistic policy options that aim to simultaneously mitigate climate change and provide positive impacts for mental health. Examples include the reduction of air pollution, increasing accessibility of active transport options, or improving energy efficiency of housing. Through tailoring and prioritizing policies that promote positive mental health outcomes, maximum impact can be achieved with cost saving benefits for governments and positive mental health benefits for populations.

Mental costs of climate change

Although research such as this, paint a promising picture for the potential of future policy, it begs the question whether the people who have the power and influence to take such action are even aware of the links between mental health and climate change? Are policymakers doing enough to protect both the planet and people’s well-being? Do they have all the facts to enable effective and impactful policy?

Our study came about as part of my postgraduate thesis project. As a masters student in experimental neuroscience, I had always been interested in the translation of neuroscience research into governmental policy and wanted to use this research project to gain a deeper understanding of this intersection. With an interdisciplinary supervisory team on board, I set out to investigate whether our decision makers, members of the UK parliament, are taking the mental health implications of climate change seriously at this pivotal moment.

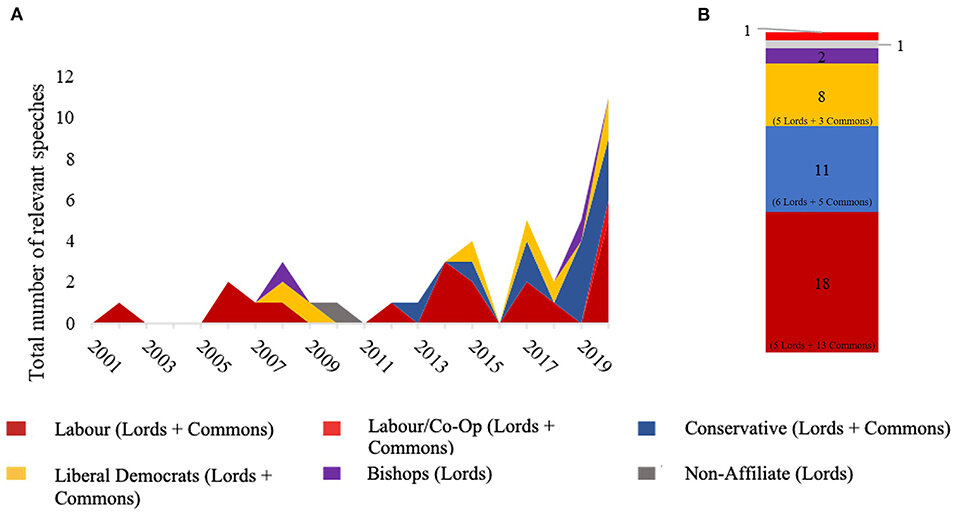

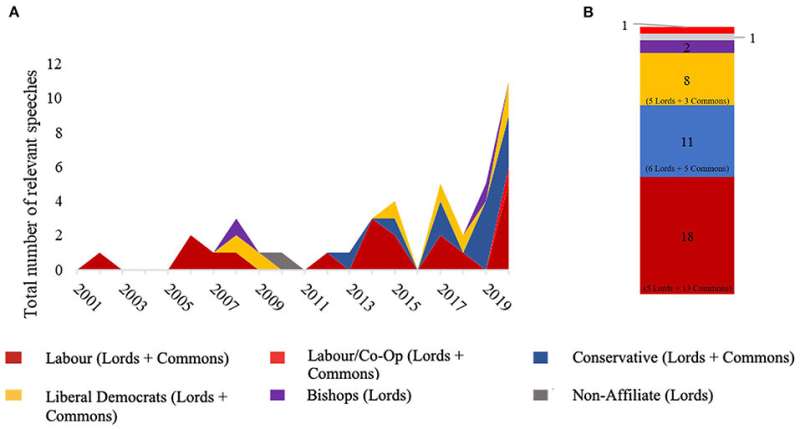

The UK Hansard database contains the official record of all UK parliamentary debates and is open source, allowing us to assess whether policy-makers have considered the links between climate change and mental health in this setting, and in what context is the issue being discussed.

After a painstaking, thorough manual review of the speech database from 2000 to 2020, the results indicated substantive gaps in parliamentary awareness of this important issue, with only 41 speeches with identifiable links between the two domains found. While climate change and mental health featured more prominently in recent debates, recognition of the full extent of mental health impacts clearly lagged behind current scientific consensus. Debates where links were made mainly made only general references to mental health and climate change, suggesting only a broad-scale acknowledgement among some decision makers of the potential connections.

We also found a number of links entirely absent from discussions. This included links between climate-related heatwaves and mental health. Interestingly, newer planetary (mental) health terms used to describe the emotional toll of climate change, including eco-anxiety and ecological grief were also not found within any speeches. Although these terms were not explicitly mentioned, parliamentarians did appear to reference indirect impacts of climate change on communities (31% of relevant speeches).

While parliamentarians might not (yet) have adopted the terminology that is commonplace in academia and public media, evidence of some conceptual integration suggests a growing understanding that climate change evokes emotional responses, can engender distress and ultimately affects mental health. Nevertheless, in absolute terms, these links were uncommonly addressed in parliamentary speeches, indicating a relative disconnect from the experiences described by growing numbers of (particularly young) people and documented by academic researchers.

The findings show that the impact of climate change on mental health and well-being has received little consideration in UK parliamentary discussions. This indicates that decision-makers may be relatively unaware of the growing evidence base on this emerging mental health crisis. Knowledge of policy-relevant issues is clearly an important prerequisite to securing effective legislation that protects the mental health and well-being of the UK and global population in the face of a changing climate.

Source: Read Full Article