Researchers from the Francis Crick Institute have studied the earliest point at which the heart forms during embryonic development and revealed, for the first time, that each part of the heart has a unique origin. Their study in mice, published in PLoS Biology today, has implications for understanding congenital heart diseases.

As an embryo develops, cells become increasingly specialized to form different tissues and organs. A key period is known as gastrulation, which leads to the formation of the main tissues of body, including the heart.

The team, a collaboration between two leading Crick developmental biology labs, identified the cells that form the heart during gastrulation and traced each individual cell’s destiny from this earliest stage until the heart had fully formed.

They found that the four chambers of the heart all have distinct spatial and temporal origins. The very first set of cells create the left ventricle, followed by cells forming the right ventricle and finally the two atria.

Jim Smith, head of the Crick’s Developmental Biology Laboratory, said: “Investigating how different types of cell in an embryo form at the right time and in the right place is crucial for understanding why this can sometimes go wrong. Congenital heart diseases affect around one in 180 babies worldwide and work like ours may help explain why just a single chamber of the heart is affected in heart defects such as left ventricle hypoplasia.”

In their study, the team first measured gene activity in individual cells, and concluded that distinct genes are active in the predecessors of the heart at very early stages of embryonic development. This means they would be allocated to distinct anatomical structures of the heart.

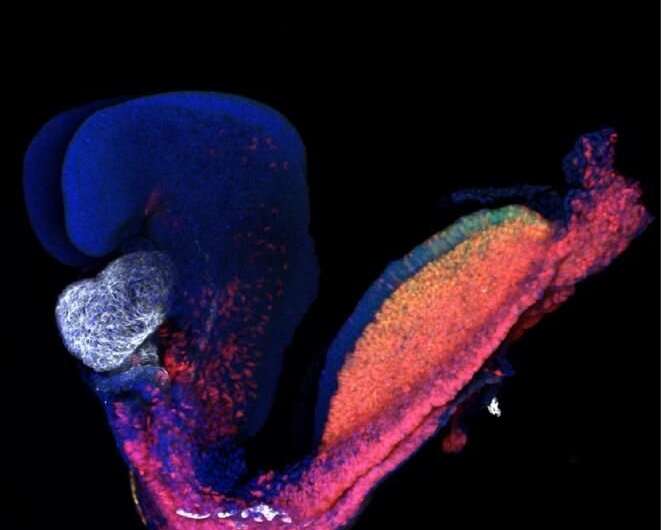

They then used an advanced imaging technique called multiphoton live-imaging to microscopically film mouse embryos developing outside the womb. They were able to follow the fate of individual cells as they migrated through the embryo to establish different parts of the heart.

Kenzo Ivanovitch, lead author and postdoctoral training fellow at the Crick, said: “Our finding that different parts of the heart arise in different locations may help researchers build better models using stem cells. Current methods produce a mix of atrial and ventricular cells which can make studying diseases that affect particular chambers of the heart more difficult.

“We can now envisage generating cells pre-determined to become specific parts of the heart and could use these to model disease or develop and test new regenerative therapies.”

James Briscoe, head of the Crick’s Developmental Dynamics Laboratory, said: “Different heart cell populations having distinct origins may mean that each group is uniquely predisposed or sensitive to genetic or environmental changes.

Source: Read Full Article