A key approach to understanding the brain is to observe the behavioral effects of turning on specific populations of neurons. One of the most popular approaches to controlling neuronal activity in model systems is called optogenetics and depends on expressing microbial light-gated channels in the neurons of interest.

These channels work as light-responsive switches, turning on neurons with a flash of light, and have been available since 2005. A critical way to confirm the function of neuronal populations would be to repeat the experiment, but this time by turning off or silencing the same neuronal subpopulations. However, the neuroscience community lacked a fast and potent way to turn off or silence neurons—until now.

Researchers at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston McGovern Medical School, Baylor College of Medicine, Rice University and the University of Guelph, Ontario, Canada, have reported a new class of light-gated channels that promise to pave the way for rapid and efficient optical neuronal silencing.

Published in Nature Neuroscience, researchers describe how they identified the first natural light-gated potassium (kalium) channel-rhodopsins (KCRs).

“A light-activated potassium channel has long been sought as a neuron silencer because potassium conductance naturally and universally hyperpolarizes neuron membranes, terminates action potentials and returns depolarized neurons to their resting membrane potential,” said lead author on the study Dr. John Spudich, Robert A Welch Distinguished Chair in chemistry at McGovern Medical School.

Using systematic screening of uncharacterized opsins (proteins that bind to light reactive chemicals) for their electrophysiological properties, researchers searched for a channel-rhodopsin with an elusive potassium-selectivity using patch clamp photocurrent screening of opsin-encoding genes with no known function expressed in HEK293 cells.

“Our screening strategy includes emphasis on opsins from organisms that differ in their metabolism and in their habitats from previously studied opsin-containing organisms, and therefore, are more likely to have evolved different opsin functions adapted to different selective pressures during their evolution,” Spudich said. “This strategy led us to two opsin-encoding genes from the sequenced genome of Hyphochytrium catenoides, a non-photosynthetic, heterotrophic fungus-like protist both phylogenetically and physiologically distant from algae containing the closely related sodium-selective CCRs.”

“We found that the two channel-rhodopsins from H. catenoides—we named HcKCR1 and HcKCR2, for H. catenoides kalium channel-rhodopsins 1 and 2—were, unlike any other known channel-rhodopsin, highly selective for potassium over sodium,” said Dr. Elena Govorunova, associate professor in the Spudich lab and first author. “In particular, the permeability ratio (PK/PNa) of 23 makes HcKCR1 a powerful hyperpolarizing tool for suppressing excitable neuron firing upon illumination.”

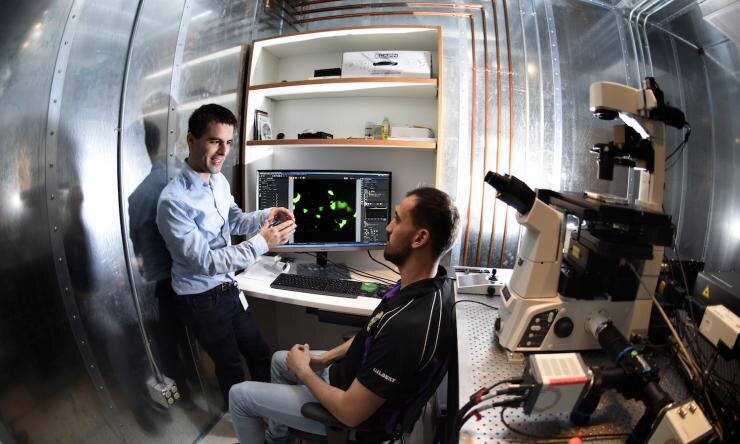

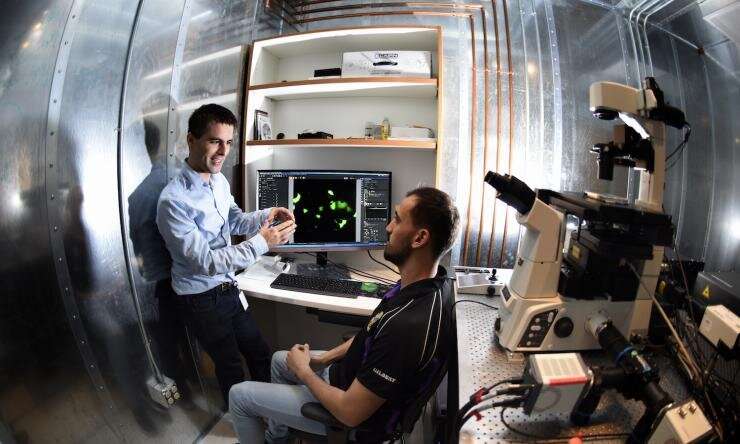

Dr. Mingshan Xue’s lab at Baylor and the Cain Foundation Laboratories, Jan and Dan Duncan Neurological Research Institute at Texas Children’s Hospital, then tested these new tools in neurons.

“When my student Yueyang Gou expressed HcKCR1 in mouse neurons and applied a flash of light, neurons became electrically silent. This channel overcomes many limitations of previous inhibitors and will be a critical tool to help us understand brain functions,” said Xue, a faculty member at Baylor and co-author on this work.

Graduate student Xiaoyu Lu in the St-Pierre lab at Baylor and Rice University then demonstrated that silencing could also be achieved using two-photon excitation, a popular technique for targeting individual neurons in vivo with high spatiotemporal resolution. “Two-photon control of KCRs may enable neuroscientists to decipher which neurons are critical for specific behaviors and when their activity is important,” said Dr. François St-Pierre, assistant professor neuroscience at Baylor and a McNair scholar, and co-author on this work.

“This work is a wonderful example of how multi-institutional collaborations in Houston produce innovative research. Houston is emerging as a premier location for developing and applying cutting-edge molecular neurotechnologies,” St-Pierre said.

Source: Read Full Article