Most countries experience substantial shortages of available organs for transplantation. Technological advancements and aging populations further expand the transplant waitlist every year.

What can we do to increase the organ supply? Researchers have proposed various schemes to boost the consent to donate, including health insurance premiums for living donors, funeral aids for surviving families and direct cash payments. However, this is where the ethical debate starts. Will financial incentives disrespect the donors by turning the selfless act into a market transaction (something most of us regard as repugnant)?

In a factorial survey experiment, I studied the impact of incentives on family overruling of presumed consent, a significant obstacle hindering organ donation. In particular, I examined two types of incentives, funeral aids and cash payments, regarding how their ethical values are perceived and how effective they are in inducing family consent for post-mortem donation.

The role of money in organ donation

Some economists have proposed that implementing a market-based system for organ transplantation, where supply meets demand at the equilibrium price, could address the persistent issues of organ shortages and long waitlists. Iran, the only country where such exchanges exist for kidney transplantation, has indeed managed to eliminate the scarcity of kidneys and the long waitlist.

While evidence from Iran and neoclassical economic principles suggest the potential benefits of introducing money into organ donation, critics across ethics, medical sciences and economics have challenged the function of money in this sensitive context.

In these arguments, organ donation constitutes fundamental altruistic values in society; thus, a cash-for-organ scheme can lead to widening inequality (as the supply would likely come from poor sellers to benefit rich recipients), causing potential donors in the current system to withdraw their goodwill, and worsening society’s ethical standards overall.

These concerns also manifest in Iran, where kidney sellers (mostly from disadvantaged backgrounds) face frequent stigmatization within their communities.

Is there a viable incentive structure that could boost organ supply without compromising ethical values? U.S. surveyees showed strong support for a central kidney exchange system, in which donors, regardless of their wealth, receive compensation from a central agency rather than directly from recipients.

Furthermore, insights from behavioral economics reveal that people are in a prosocial mindset when their acts are rewarded with a gift, but switch to a more pro-self mindset when receiving cash payments or a gift coupled with a monetary value.

Study design

Employing a full factorial design, my study presented 756 U.S. subjects with hypothetical scenarios, wherein they are requested to make organ-donation decisions for a recently deceased family member. Each vignette varied in the characteristics of the potential donor: age (25, 40, and 55), gender (brother or sister), death type (brain or circulatory death) and recorded wish to donate (yes, no, or unclear).

Each participant was randomly assigned to one of seven incentive conditions across four categories: gift rewards (an honorary casket or a full funeral service), monetized gift rewards (a $2,500 casket or a $7,500 funeral service), direct payments ($2,500 or $7,500 in cash), and no rewards (the control). Participants were further reminded that they would be the one paying for the funeral of the deceased family member.

Following the vignette, subjects evaluated the reward presented to them in seven ethical criteria: (1) maintaining the concept of organ donation as a gift from the donor to the recipient, (2) conveying gratitude for the donation, (3) honoring the deceased donor, (4) preserving voluntariness, (5) keeping away organ commercialization, (6) upholding current altruistic values and (7) maintaining society’s positive view of organ donation. Last, I asked participants to indicate their willingness to grant family consent for post-mortem donation, based on the entire vignette and incentive conditions that they saw.

Results

Participants judged funeral benefits (an honorary casket or a full funeral service), whether coupled with monetary values or not, substantially higher than cash rewards in the all-ethical criteria.

Most important, a funeral service without a disclosed value led to a 8.5% increase in family consent for post-mortem donation compared to the existing system. With weak significance, a funeral service coupled with a $7,500 price tag still boosted consent level by 7.8%. An 8.5% increase could bring about an addition of 1,000 donors annually, or 20,000 donors since 1988.

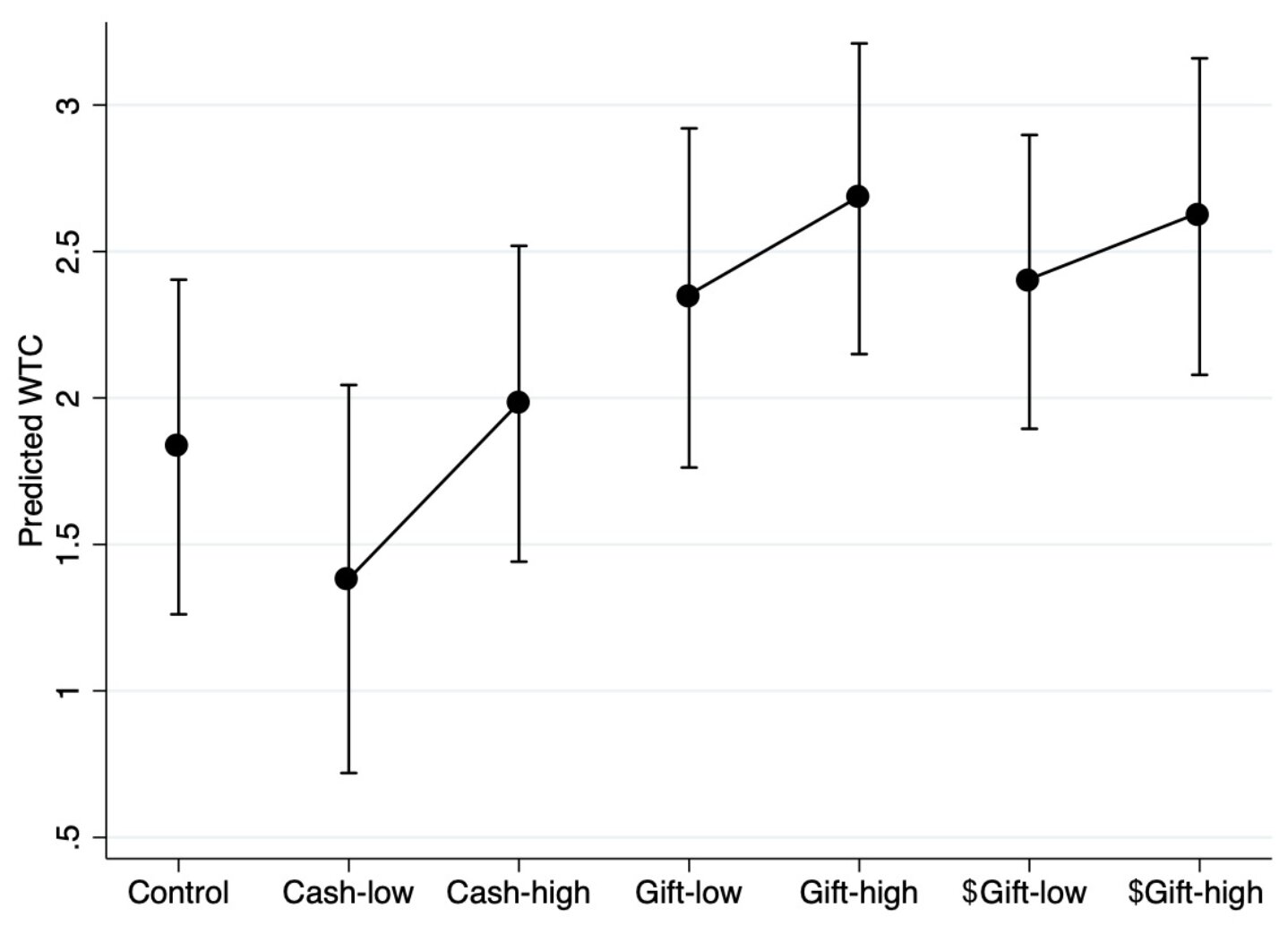

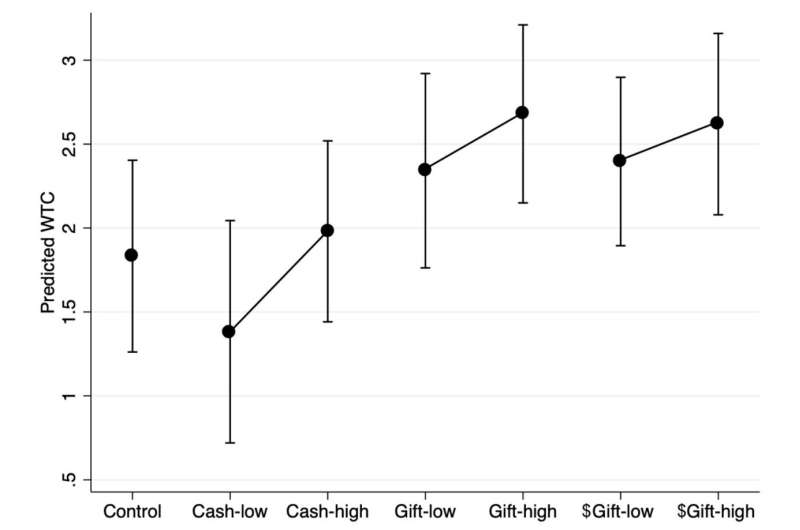

The figure above, which visualizes the predicted consent rate for each reward condition, suggests a potential price sensitivity between low and high incentives, especially between the two cash prizes. However, statistical analysis fell short of confirming the significance of this trend.

Among sociodemographic factors, only the donor status was found to strongly influence judgments, as registered donors rated rewards more favorably and indicated higher willingness to provide consent than those who had never considered becoming donors.

Conclusion

Without a doubt, incentivizing organ donation is highly controversial: it raises ethical questions about turning organ donation into a transaction and potentially undermining its altruistic nature. Finding a balance between boosting organ supply and upholding ethical standards is a challenging aspect of this ongoing debate.

This study, published in Review of Behavioral Economics, suggests that offering a funeral service to the deceased donor could strike this balance by expressing gratitude for the donation and honoring the deceased, while potentially reaching higher levels of consent from surviving families.

This story is part of Science X Dialog, where researchers can report findings from their published research articles. Visit this page for information about ScienceX Dialog and how to participate.

More information:

Vinh Pham, Cash, Funeral Benefits or Nothing at All: How to Incentivize Family Consent for Organ Donation, Review of Behavioral Economics (2021). DOI: 10.1561/105.00000136

Tuan Vinh Pham is a researcher at the Graduate School of Economics, Waseda University, Japan. Pham’s research fields include experimental economics, behavioral economics, development economics and political economy. Currently, Pham’s research at Waseda University centers on examining the conflict between equality and efficiency in cooperative bargaining. Pham is also actively involved in experimental studies on incentives, norms and prosociality and is working toward conducing field experiments on economic behaviors in Vietnam, Pham’s home country.

Source: Read Full Article