Going on a weight-loss diet when you’re not obese RAISES your risk of diabetes and makes you MORE likely to pile on the pounds later in life, major study warns

- Harvard University researchers looked at people who lost at least 10lbs (4.5kg)

- They were split into lean, overweight or obese groups based on their BMI

- Results showed lean people who did extreme weight loss re-gained more easily

- They were also more likely to suffer from type 2 diabetes, the scientists said

Going on a dramatic weight loss diet when you’re not obese could actually harm your health years later, a major study suggests.

People already quite lean who lost 10lbs (4.5kg) were at a higher risk of Type 2 diabetesa decade later compared to their peers who didn’t go on an extreme diet.

They were also more likely to pile on the pounds further down the line, according to the research by Harvard University.

The scientists said their results were ‘surprising’.

But they believed lean people who underwent dramatic weight loss had higher levels of hunger hormones, making them more likely to crave junk food, and could gain fat more easily.

Many skinny people attempt to lose fat in hope of achieving the ‘Instagram’-style washboard abs or a more toned physique.

But the team at Harvard is now warning that dramatic weight loss should be used only by those who ‘medically need them’.

Results also showed that lean people who lost their weight by following a fad diet or commercial weight loss programme were most likely to get fat later in life.

About 40 percent of American adults are overweight, but a study from Massachusetts University found as many as half of women and 20 percent of men who are lean believe they also fall into this category.

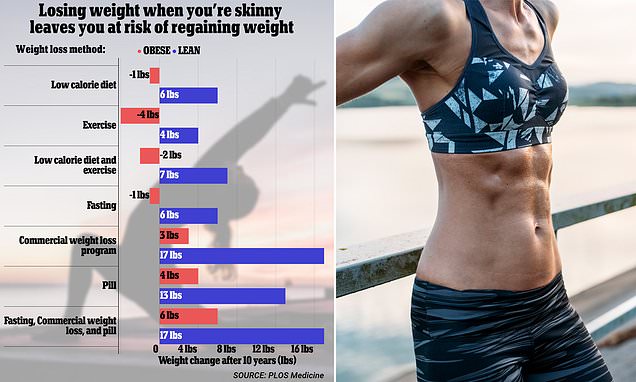

Scientists at Harvard University tracked people for a decade after they lost 9.9lbs (4.5kg). They were split by where they were lean (blue bars) or obese (red bars) at the start of the study, and by weight-loss method (left hand side labels). Each group was then compared to other participants in the same category who did not try to do extreme weight loss. Results showed lean people who did extreme weight loss were likely to be heavier than their peers a decade later, while for obese people it had the opposite effect

Many lean people try to cut their weight with the aim of achieving washboard abs and ‘Instagram-ready’ toned bodies. But the scientists warned this was bad for their health

In what is believed to be the first study of its kind, experts looked at data for 200,000 healthy Americans collected between 1988 and 2017.

Nine in ten participants were female.

They were divided by body mass index (BMI) into those that were lean — had a healthy or underweight range — overweight, or obese.

A healthy BMI means someone likely has a good body fat to height ratio that is not putting them at risk of obesity-related diseases like high blood pressure.

Body mass index (BMI) is a measure of body fat based on your weight in relation to your height.

Standard Formula:

- BMI = (weight in pounds / (height in inches x height in inches)) x 703

Metric Formula:

- BMI = (weight in kilograms / (height in meters x height in meters))

Measurements:

- Under 18.5: Underweight

- 18.5 – 24.9: Healthy

- 25 – 29.9: Overweight

- 30 – 39.9: Obese

- 40+: Morbidly obese

Each was then split into two groups — those who lost 9.9 pounds (lbs) (or 4.5 kilograms, kg) — within a four-year time frame and those who did not.

Weight watchers were also asked to say how they lost weight and split into seven groups — a low-calorie diet; exercise; low-calorie diet plus exercise; fasting; commercial weight loss program; diet pills and a combination of fasting, commercial and diet pills (FCP).

Scientists then followed up with participants medical records for another 10 years, on average.

Among lean people, those who went on an extreme diet put on between 4.4 and 17 more pounds (2 to 7.7kg) than their peers.

But among obese people, those who did four of the programs — low calorie diet, exercise, low calorie diet and exercise and fasting — kept off between 3.5 and 1.3 more pounds (1.2 to 0.5kgs) than their peers.

In the three others — commercial weight loss plan, pill and FCP — obese people did not gain more than 6.2lbs (2.8kg) extra compared to their peers.

Among lean people, none of the plans led to greater weight loss a decade later than if they had done nothing.

This was the same for the overweight group, where they put on up to 15lbs (7kg) more than their peers.

The scientists also looked at the diabetes risk for participants.

Lean people who went through dramatic weight loss were up to 54 percent more likely to get type 2 diabetes than their peers.

But all the obese adults who did the plans were less likely to develop diabetes than their peers.

The scientists did not calculate average figures between those who did different weight loss plans but fell into the weight category.

Overweight adults who lost weight rapidly were up to 42 percent more likely to get diabetes than their peers.

Dr Qi Sun, a Harvard epidemiologist who led the study, said: ‘We were a bit surprised when we first saw the positive associations of weight loss attempts with faster weight gain and higher type 2 diabetes risk among lean individuals.

‘However, we now know that such observations are supported by biology that unfortunately entails adverse health outcomes when lean individuals try to lose weight intentionally.

‘The good news is that individuals with obesity will clearly benefit from losing a few pounds, and the health benefits last even when the weight loss is temporary.’

He said that weight loss likely led to biological changes in lean people that put them at higher risk of piling on the pounds later.

It may raise the levels of hunger hormone ghrelin, leading to someone being hungry more often.

This can also make people more likely to reach for salty or sugary foods because it activates the region of the brain associated with rewards.

Similarly, the researchers warned more fat cells — which release ghrelin — may accumulate in lean people in order to boost this hormone’s levels.

At the same time, rapid weight loss led to lower levels of anorexigenic hormones — like leptin — that help to suppress hunger.

Studies also suggest it leads to the body reducing the amount of energy it burns, to ensure more energy is conserved.

Source: Read Full Article