Your pancreas is a little sweet potato-shaped organ that sits snug behind your stomach. The pancreas is studded with islets, the cell clusters that house insulin-producing beta cells. In people with type 1 diabetes, the body’s own immune cells head for the islets and start attacking the beta cells. No one knows exactly what triggers this attack.

One clue may lie in the pattern of beta cell death. Many beta cells are killed off in big patches while other beta cells are mysteriously untouched. Something seems to be drawing immune cells to attack specific groups of beta cells while ignoring others.

In a new Science Advances study, researchers at La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) report that the nervous system may be driving this patchy cell die-off. Their new findings in a mouse model suggest that blocking nerve signals to the pancreas could stop patients from ever developing type 1 diabetes.

“It’s astonishing that this process may be stoppable through neuronal influence,” says LJI Professor Matthias von Herrath, M.D., who served as the study’s senior author.

The von Herrath Lab has been working to uncover the cause of type 1 diabetes. Although there are environmental and genetic risk factors for the disease, type 1 diabetes often seemingly strikes at random. Over the years, researchers have sought an explanation for the observed patchy pattern of cell death. One theory has been that these patches have differences in blood flow or they have been damaged by a virus that might be sparking an immune attack.

But recently, researchers have been exploring a new field called neuroimmunology, which is the idea that nerve signals can affect immune cells. Could nerve signals drive immune cells to attack certain areas of the pancreas?

“We thought that could explain a lot,” says study first author Gustaf Christoffersson, Ph.D., a former LJI postdoctoral researcher now at the University Uppsala, Sweden.

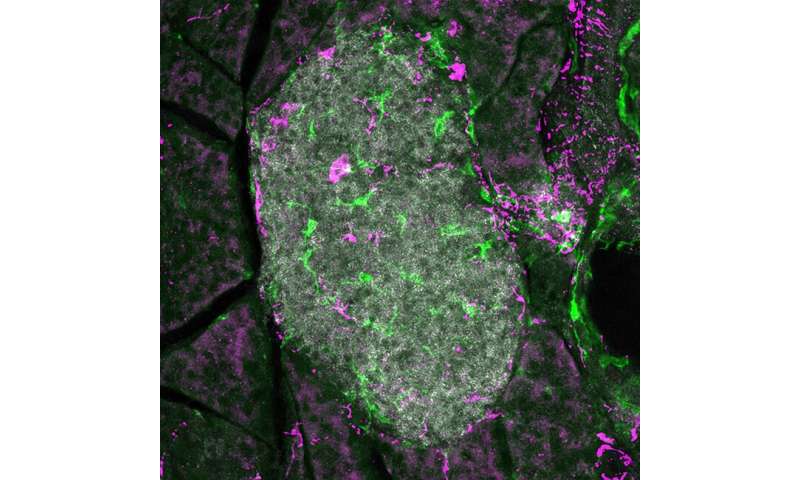

To test this theory, the researchers used a mouse model that can be experimentally induced to have beta cell death. They “denervated” the mice, either surgically or through use of a neurotoxin or a pharmacological agent, to block most of the sympathetic nerve signals to the pancreas. The researchers then used LJI’s world-class imaging facility to track the pattern of beta cell death in living mice.

The team found that blocking the nerve signals protected mice from beta cell death, compared with no effect in mice given no treatment and mice given only beta blockers. Without innervation, it was like the pancreas had gone dark and immune cells were unable to find their targets

“We were pretty surprised to see that these nerve blockers led to pretty significant differences in the onset of diabetes,” says Christoffersson.

More work needs to be done before this method can be tested in people. Von Herrath explains that doctors would first need a reliable way to identify patients at risk of type 1 diabetes onset. Once these patients are identified, von Herrath believes they could be treated either through electrostimulation or drugs to block nerve signals. There are also non-surgical, intravascular methods for blocking nerve signals.

The new discovery might explain much more than the patchiness seen in type 1 diabetes. Several autoimmune diseases share this same patchiness—but in a symmetrical pattern. For example, the skin condition vitiligo causes skin to lose its pigment, often in symmetrical areas across the faces and hands. Arthritis also tends to strike symmetrically, with inflammation in both knee, elbow or wrist joints.

The new study suggests that these areas may be innervated by nerves that branch out symmetrically through the body.

“This symmetry is very striking, and it’s been almost impossible to explain,” says von Herrath.

Source: Read Full Article