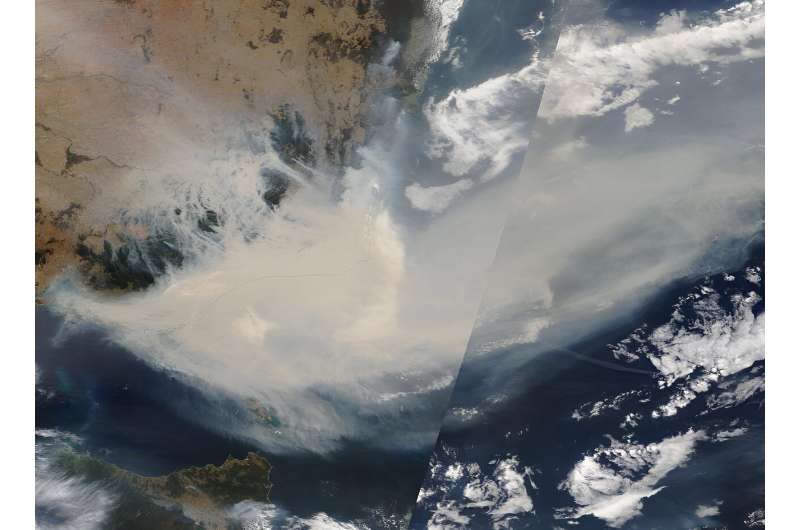

Smoke covered large swathes of Australia during the catastrophic summer fires of 2019-2020. You could see the plumes from space. Over 20% of Australia’s forests went up in smoke and flame.

As the fires spread, smoke covered towns and cities. Millions of people were suddenly confronted with bad air. Many had children. Many were pregnant. All worried about what the smoke might mean for their child.

Our new book explores the worries and desperation of people who were pregnant or parenting during the unprecedented fires over the 2019–2020 summer. We drew on in-depth stories from 25 mothers (and sometimes their partners).

The smoke was something they had no control over. But public health advice told them they had the responsibility to keep their child safe. Mothers and their partners worried endlessly about what damage the pollutants in the air were doing. This, we argue, speaks to how those who have done little to fuel the climate crisis can be particularly at risk.

What did we find?

One woman, Renee, told us about the anxiety of being pregnant and with two small children in the smoke:

“I was really worried about lung damage for my kids upstairs, but I was also worried, [for] like, brain development at that point, as you get into the end of the pregnancy […] I kept having conversations with myself going, “I’m not in my first 12 weeks, surely that’s riskier. I’m in this safer zone.'”

Renee’s story speaks to how our interviewees tried to take responsibility for themselves and their fetuses.

It was a common thread. The 25 mothers and partners we interviewed were living in Canberra or on the south coast of New South Wales. These areas were among the worst affected by smoke.

Renee’s feelings of risk and responsibility are amplified in an era that historian of fire Stephen Pyne has named the “Pyrocene,” a time when bushfires and the burning of fossil fuels are careering out of control.

Our research shows pregnant people were framed as “doubly vulnerable” to smoke, due to their own exposure and that of their fetus. Health advice from organizations such as the Royal Women’s Hospital urged them to stay indoors, use air-conditioning and to spend time at libraries and shopping centers to avoid exposure.

Who is responsible?

Given health warnings about smoke exposure, it’s not surprising our interviewees expressed considerable concern for their unborn babies.

Alice, pregnant during the fires:

“It was really constantly on my mind, and I tried to kind of not get too anxious about it, but it was really difficult because […] I mean, you just think about it all the time. You’re just constantly worrying when you’re pregnant what’s going to affect the baby. Like everything you do.”

Gina, pregnant during the fires:

“It was just always kind of lingering, like we were just unsure about what kind of effects it would have on the development of his organs and whatever else. I was obviously more stressed than my husband, just because, you know, the mother is carrying the baby and there’s more stress just naturally on the mum.”

Even while worrying about the health of their babies, women also felt the responsibility for keeping them “safe” from smoke exposure fell primarily to them.

What we ask is—is this fair? As recent research makes clear, pollutants such as bushfire smoke are uncontrollable.

Feminist scholars note that public health advice and scientific research tends to emphasize how vulnerable the fetus is and, by extension, place responsibility on the mother—even while acknowledging how little control they have over the situation.

When responsibility meets uncertainty

Australia has long been affected by bushfires. But they’re getting worse as the world heats up.

There’s no roadmap for how to live with sudden crises such as fires or the long, slow burn of incremental change. We’re all experimenting at individual, household and community levels as well as nationally and regionally.

Many of us are having to tinker with our machines and our homes to take care of others and to survive the new extremes.

Climate change is happening to the globe. But the devastation wreaked by extreme weather, disruption to farming or intensified fires is not evenly distributed, either by who did the most to cause it or by who is most hard hit.

Wealth magnifies unfairness. Those who have done the most to create and benefit from carbon-intensive capitalism are more likely to be able to shield themselves from its effects, while people who are pregnant and parenting, and First Nations people—especially children aged five and under—are more vulnerable.

What we point to is a question. How can we find ways to take care of fetuses and young children without forcing parents (and mothers, in particular) to shoulder the impossible responsibility of safety?

Provided by

The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Source: Read Full Article