In talk therapy, words matter. Psychotherapists must not only choose their words carefully, but also decide how and when to say them. “These are choices every clinician has to make, in the moment, alone,” says Adam Miner, a licensed clinical psychologist, epidemiologist, Stanford HAI affiliate, and clinical assistant professor in psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford School of Medicine.

As a result, there is a high degree of variability in how therapy is provided, making it difficult to know what aspects of treatment are beneficial.

“We know psychotherapy is effective,” Miner says, “but we really struggle to find differences between therapies, and we don’t really know what accounts for patient improvement in terms of moment-to-moment language.”

Until now, trying to understand what works in psychotherapy has been like studying the effect of a medication without knowing if it was properly manufactured, prescribed at the correct dosage, or consistently administered, says Scott Fleming, a graduate student in Stanford’s Biomedical Informatics Training Program. “The very first step in being able to identify what makes therapists effective,” he adds, “is identifying what therapists actually do and what makes different therapists different.”

To address that question, Miner, Fleming, and several colleagues including Bruce Arnow, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, and Fleming’s advisor, Nigam Shah, professor of medicine, developed a natural language processing tool kit called CRSTL (Computational RepresentationS of Therapist Language) that distills transcribed psychotherapy sessions into 16 quantifiable features that can be further analyzed using AI.

The features include the frequency with which therapists use first-, second-, or third-person pronouns; express a past, present, or future orientation; refer to negative or positive emotions; check for understanding; use absolutist terms; and hedge their comments (by using words like perhaps, probably, seems, or sometimes). The team also measured how much time therapists speak during a session as well as how fast they speak.

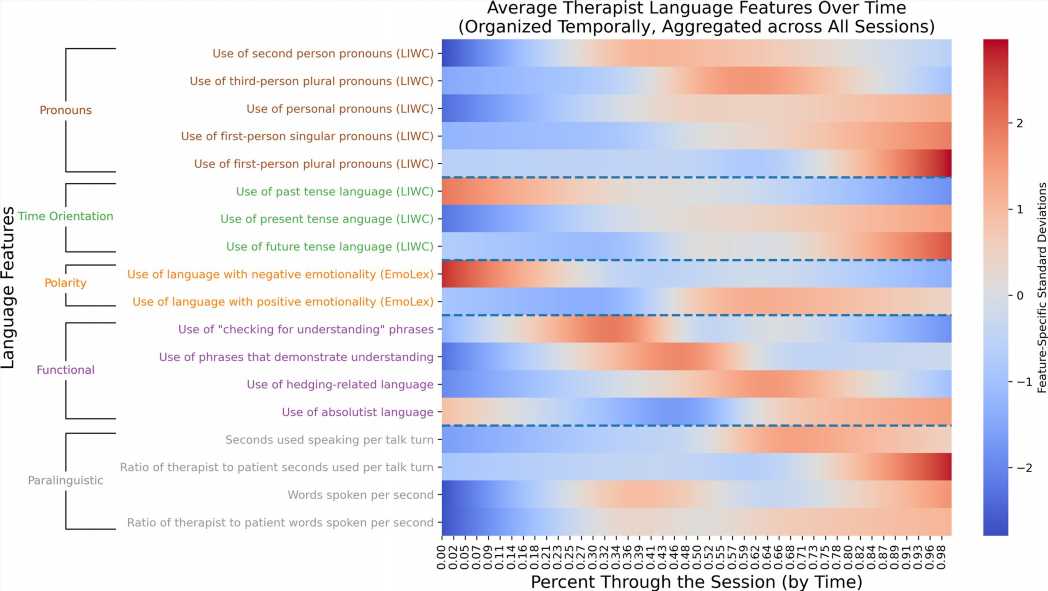

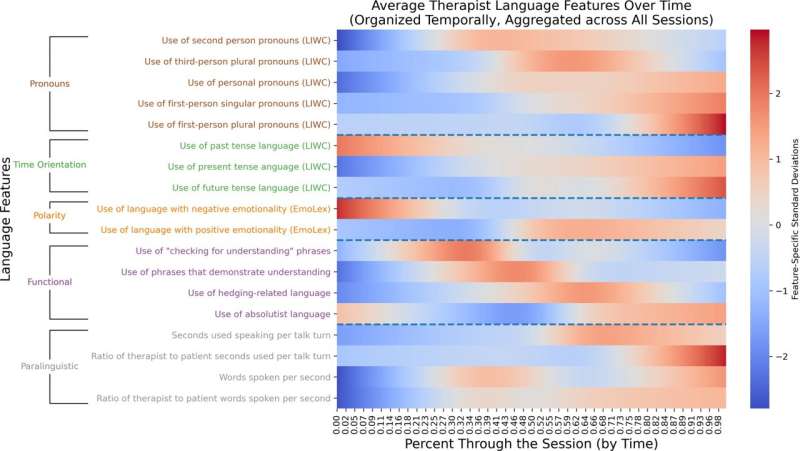

The CRSTL tool kit then allows researchers to study how these features change over the course of a session (timing); how they change in response to the patient’s use of language (responsiveness); and how they differ from session to session and therapist to therapist (consistency).

Among the team’s findings, published in a new paper in Mental Health Research: Therapists’ language use changes from the beginning to the end of a therapy session, sometimes converges and sometimes diverges from patients’ language use, and differs more between therapists than across sessions with the same therapist. To encourage future work in hypothesis generation and testing, the team has released their code as open source on Github.

These findings suggest that analyzing therapist language may hold promise for understanding what contributes to effective psychotherapy sessions and patient prognosis. “Quantification of language use was the bottleneck here,” Fleming says. “And we’re really excited about the analysis it enables.”

Key goals of future work include determining whether certain patterns of therapist speech lead to improved or worsened outcomes for patients, as well as exploring whether therapists can modify those patterns to provide better care.

AI opens new possibilities for analyzing therapy transcripts more deeply and at scale, says Miner, who has been researching various ways the technology could be used to improve mental health care. “With the right privacy and consent pieces in place, we can quantify the features that may relate to prognosis or therapeutic rapport but have yet to be connected to language.”

Moneyball for therapy

In the past, to assess what makes individual therapists effective, researchers would either observe sessions in person or review tapes or transcripts to identify aspects of a therapist’s behavior they deemed noteworthy, searching for patterns. The approach was hit or miss, labor intensive, and subjective.

More recently, some researchers, including Miner, have used AI to rate aspects of mental health support that are hard to quantify, such as expressions of empathy or compassion. But these ratings are something of a black box, Fleming says. It’s not entirely clear what the AI is measuring or how to alter a therapist’s words to make them more compassionate or empathetic.

While there’s a place for these more complex models, Fleming says, the CRSTL team wanted to focus on features that are inspectable, can be easily quantified, and are modifiable by the therapist. Indeed, each of the 16 features they chose to measure is very concrete: The specific words being measured are based on previous psychotherapy research, clearly identified, and codified in the software.

The chosen features are also modifiable by therapists. “Once we can assess the degree to which differences in language track with patient trajectories, we want to develop insights that can be used to improve patient care,” Fleming says.

Fleming compares CRSTL to baseball’s shift toward quantifying player performance as captured in the bestselling book and Oscar-nominated movie Moneyball. “The establishment and automated calculation of metrics in the baseball space enabled rigorous analysis of which features were most important for generating wins. Our hope is that the quantification and rigorous analysis of psychotherapist language features will enable ‘wins’—i.e., improved therapy outcomes—in the psychotherapy setting.”

Quantifying therapeutic language

For CRSTL, Fleming, Miner, and their colleagues generated a list of clinically relevant language features that fall into five broad domains: pronouns, time orientation, emotional polarity, specific tactics, and paralinguistics (the way something is said, such as speed, volume or pitch, rather than the words themselves).

Why these features and domains? Each is based on prior research. For example, Miner says, “In prior work by other researchers, we’ve seen increased use of first-person pronouns by people who are depressed.” Pronoun use is also easy to measure and could reveal a lack of social support in the patient’s life or a depressed person’s tendency to focus inward.

Similarly, a focus on the past rather than the present or future is linguistically measurable and might reflect a person’s mental state. “A depressed patient might spend a lot of time using past-tense language, and the therapist might want to help them talk about the future to instill hope,” Miner says.

Once they identified the features, the team used AI to extract them from 78 transcribed therapy sessions involving that same number of unique patients and unique therapists. An additional 20 transcripts represented a second session involving a therapist from the first data set interacting with a different patient.

For each feature, the team looked for patterns related to three larger themes: therapists’ timing, responsiveness, and consistency—all of which have proven difficult to quantify in the past, Miner says.

With respect to timing, the team found that over the course of a session, therapists shift toward using more personal pronouns, more present- and future-oriented than past-oriented words, and fewer emotionally negative words. As the session went on, therapists also spoke more rapidly and for longer durations.

To evaluate therapists’ responsiveness, the team looked at how therapists modulated their speech in response to fluctuations in patients’ speech patterns. For example, in response to patients who spoke quickly, many therapists slowed their rate of speech.

“Divergence or convergence is a really important idea,” Miner says. Clinicians must decide when to create rapport with a patient by matching their emotionality or tone and when to do the opposite, he says. For example, if the patient says everything is bad and will never get better, the therapist could validate that feeling by using similar language or soften it by using less absolutist terms. By capturing both divergence and convergence, this work could help researchers understand which approach is more beneficial in a particular context.

To look at consistency, the team compared how a single therapist used language from one session to another and also how each individual therapist’s language compared to that of other therapists. Their findings: Language use was more consistent when the team compared sessions led by the same person than when they compared sessions led by different therapists. This suggests that therapists have patterns in the ways they talk with patients that are true across different patients. If these language-use signatures are borne out in future work, it suggests these could be targeted for modification if, down the road, a particular aspect of a signature is found to correlate with better or worse outcomes, Fleming says.

Helping therapists help their patients

The team has not yet studied whether therapists’ language use translates to better care, but they expect that to be the case. “We would hope that if clinicians are doing good work and patients are getting better, we would see those changes expressed in language,” Miner says.

They also hope to explore how different therapeutic protocols are implemented. Many psychotherapy interventions or schools of thought overlap both conceptually and in practice and we don’t really know what therapists are saying when they are in the room with a patient, Miner says. Do therapists who provide cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) use language differently than those offering psychoanalysis or integrative/holistic therapy? And among people providing CBT, is language use the same or different when treating people for different mental health conditions such as depression, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia? “We have struggled to define the essential features of one school of thought versus another,” Miner says. “And we’re hoping CRSTL can help that.”

Miner also sees the potential for CRSTL to improve new clinician training. Currently, he says, clinicians are trained at a high level and more thematically. “We might, for example, suggest they be sensitive to a patient’s rate of speech, but that doesn’t help them in the moment to know when and how to do it.” The CRSTL tool kit might change that by enabling analysis of a trainee’s sessions. If, for instance, a trainee speaks too quickly and too much, causing stress or confusion for patients, the tool kit could reveal that, Miner says.

Source: Read Full Article