Fluoridation of the water supply may confer a modest benefit to the dental health of children, a seven-year-study led by University of Manchester researchers has concluded.

However, the benefits are smaller than shown in previous studies—carried out 50 years ago—when fluoride toothpaste was less widely available in the U.K.

The CATFISH study is published today (Nov. 14) in the journal Public Health Research.

The research was led by a team from the University’s Division of Dentistry, and is the first contemporary study of the effects of initiation of a water fluoridation scheme in the U.K. since fluoride toothpaste became widely available in the 1970s.

The study also showed it was likely that water fluoridation was a cost effective way to help reduce some of the £1.7 billion a year the NHS spends on dental caries.

Other collaborators on the study included Cambridge University, Kings College London, Salford Royal Foundation Trust and the specialist dental services at North Cumbria Integrated Care NHS Foundation Trust.

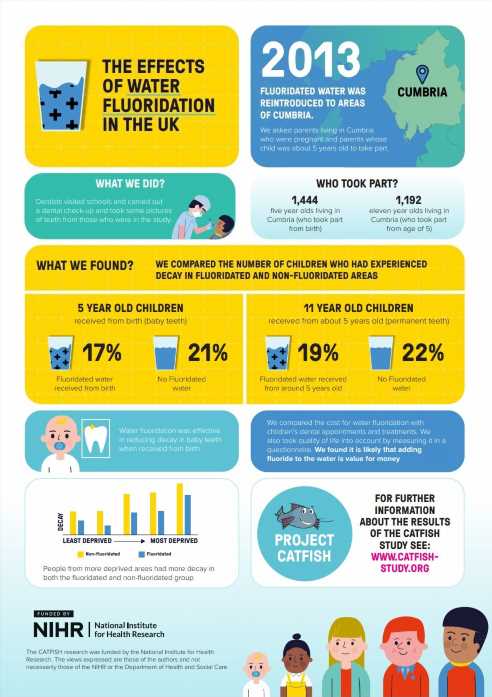

The study assessed the dental health of two cohorts of young children over a six year period in West Cumbria —where water fluoridation was reintroduced in 2013, and the rest of Cumbria, which remains fluoride free.

In West Cumbria, the younger cohort were born after water fluoridation was introduced (this meant they had the full effect of water fluoridation).

The older cohort was aged around five when fluoride was reintroduced into the water supply—which meant they mainly received the benefit for those teeth already in the mouth.

At the end of the study, 1,444 five-year-olds who were part of the younger cohort and 1,192 eleven-year-olds who were part of the older cohort had taken part.

Dental teams carried out examinations on the children at regular intervals and took images of their teeth which were blinded to the fluoridation status of each participant to remove bias.

They also collected information about the children’s diet, brushing habits and dental attendance.

In the younger cohort, 17.4% of the children in fluoridated areas had decayed, filled or missing milk teeth; the number was 21.4% for children in non-fluoridated areas, amounting to a modest 4% reduction in incidence of caries.

In the older cohort, 19.1% of the children in fluoridated areas had decayed, filled or missing permanent teeth; the number was 21.9% for children in non-fluoridated areas. There was insufficient evidence as to whether water fluoridation prevents decay in older children with a difference of 2.8%.

Over the last 40 years the proportion of children affected by decay has fallen dramatically.

But because tooth decay falls disproportionately on more disadvantaged groups, fluoridation should be considered alongside measures targeted at vulnerable populations, the team argue.

Professor Mike Kelly, senior member of the research team from The University of Cambridge said, “Health inequalities are a feature of all societies, including the U.K. The poor dental health of children from the most disadvantaged communities and the excess number of children having general anesthetics each year still needs to be addressed. We need to continually look at measures which can help prevent the unnecessary burden of pain and suffering.”

Dr. Michaela Goodwin from The University of Manchester, senior investigator on the project said, “While water fluoridation is likely to be cost effective and has demonstrated an improvement in oral health it should be carefully considered along with other options, particularly as the disease becomes concentrated in particular groups.

“Tooth decay is a non-trivial disease which is why measures to tackle it are so important. The extraction of children’s teeth under general anesthetic is risky to the child and is the most common reason for children between the ages of 5 and 9 to have a general anesthetic.”

“Decayed teeth are painful and can impact on sleep patterns, learning, attention and many aspects of general health.”

Source: Read Full Article