Medicine has made huge progress in the fight against cancer. In the past three decades, the average person’s risk of dying from cancer in the United States has decreased by 32%, thanks to factors like earlier detection and advances in drug treatment.

Still, while increasing survival rates are encouraging, cancer remains prevalent. According to the American Cancer Society, cancer is the second most common cause of death in the U.S., after heart disease. And scientists continue to look for ways to turn the tide against cancer.

Now those doctors and researchers have gained access to a new tool with the power to offer better insights into how tumors respond to treatments.

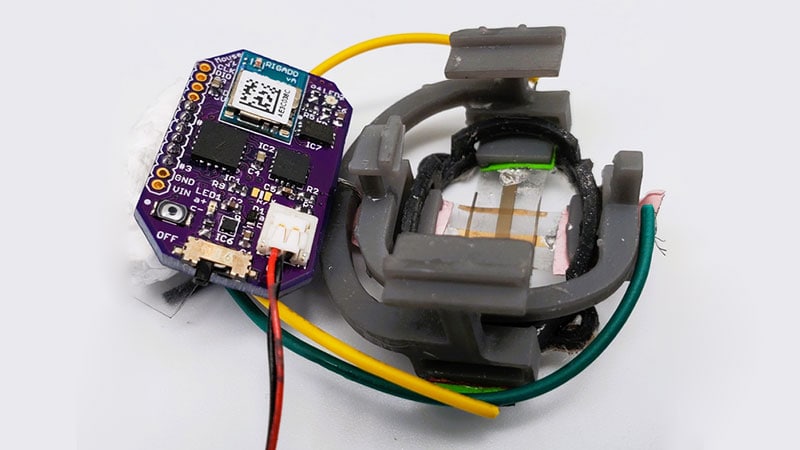

That tool is a first-of-its-kind wearable device that can tell in real time how much a tumor is growing or shrinking, sending those results wirelessly to a smartphone for analysis. The device has been proven and is already being used in animal studies.

“Our technology is the first bioelectronic device to monitor tumor regression, and the first technology to monitor tumors in real time,” says Alex Abramson, PhD, assistant professor in the chemical and biomolecular engineering department at Georgia Tech and a co-author of a new study of the device.

The sensor uses technology similar to other flexible skin-like wearable devices capable of capturing biometric data, including through sweat. But what makes this sensor unique is the chemical element enabling it to detect those tumor changes: gold.

Gold is a useful material because it is flexible and conductive. In the new monitors, a gold-infused sensor is stuck to the skin around the tumor to be measured. If the tumor grows, the gold coating cracks and becomes less conductive. As the tumor shrinks, those fissures close and the material becomes more conductive.

“We measure these changes in conductivity, and we translate this into measurements of changes in tumor volume,” Abramson says.

Currently, the most used methods for measuring tumor size are calipers or bioluminescence imaging (BLI). These measurements are useful and accurate, but are typically performed every few days or weeks. The new sensor captures updates every five minutes — and can also detect extremely small changes that calipers and BLI can’t.

“Our sensor will allow us to better understand the short-term effects of drugs on tumors and allow scientists and healthcare professionals a more streamlined method to screen drugs that could become therapies in the future,” Abramson says.

The sensors are already available for use in animal studies, though it will take several years before they’re made for human use. And they cost less than you might imagine for something containing gold. “The sensor can be made by a researcher for less than $60,” Abramson adds.

Sources:

Alex Abramson, PhD, assistant professor in the chemical and biomolecular engineering department at Georgia Tech

Science Advances (2022). A flexible electronic strain sensor for the real-time monitoring of tumor regression.

Source: Read Full Article