Decades after racially discriminatory housing and lending practices were outlawed, new research suggests historical neighborhood redlining continues to affect cardiometabolic health and related risk factors.

“Policies that were started in the 1930s continue to have a really significant impact on shaping the cardiovascular health of an entire nation,” senior author Sadeer Al-Kindi, MD, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio, said.

“We’re hoping to shed a little bit more light into this, so we can move the needle, hopefully, towards improving health outcomes and reducing disparities,” he told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology.

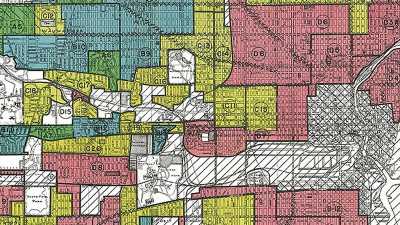

The term redlining comes from the 1930s color-coded federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) maps that ranked the loan worthiness of neighborhoods in nearly 200 cities across the United States. Areas were graded as A (“best” or green), B (“still desirable” or blue), C (“definitely declining” or yellow), and D (“hazardous” or red).

While redlining was banned in the 1960s, it buttressed segregation in American cities for generations and has been linked with contemporary health inequities including asthma, certain types of cancer, preterm birth, mental health, and other chronic diseases.

A 2021 MESA analysis of about 4800 adults in six US cities found that Black adults living in historically redlined areas had a lower cardiovascular health score than Blacks in A-graded, green areas.

The present study extends that work by examining health indicators in the CDC’s PLACES database for 38.5 million US residents across 11,178 HOLC-graded census tracts in the Midwest, Northeast, South, and West. The researchers also linked census tract-level exposure to particulate matter greater than 2.5 µm and diesel particulate matter as potential environmental confounders.

In each region, the percentage of Black and Hispanic residents was lowest in green HOLC areas (13.2% and 8.5%, respectively) and highest in red HOLC areas (32.2% and 28.8%, respectively).

As reported July 4 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, significant increases were found across HOLC grades green to red in the prevalence of: diabetes (from 9.2% to 13.5%), smoking (13.1% to 20.6%), obesity (28.5% to 36.3%), hypertension (30.0% to 33.6%), coronary artery disease [CAD] (5.3% to 6.2%), stroke (2.9% to 4.2%), and chronic kidney disease [CKD] (2.7% to 3.6%; P <.001 for all). Only high cholesterol went in the opposite direction, dropping from 31.3% in green areas to 29.2% in red areas (P < .001).

The associations between neighborhood areas and CAD, stroke, and CKD were weakened but remained statistically significant in the fully adjusted model, which included comorbidities, risk factors, demographic composition, as well as environmental exposures.

The associations were largely consistent across regions; however, Southern and Northeastern states had the largest gap between HOLC red and green areas for CAD (1.8% vs 41.5%), stroke (23.3% vs 86.2%), and CKD (18.5% vs 59.3%).

“This is what I was expecting but I didn’t expect the magnitude of the association to be this strong,” Al-Kindi said. “But it goes in line with prior studies that showed a relationship between various health outcomes, lung disease, other diseases, within each category of neighborhood risk.”

The observational study can’t explain the reasons for the disparities but they may be related to lack of access to care, unhealthy behaviors, psychological stress from racial discrimination and financial strain, and disproportionately higher exposures to nearby sources of environmental pollution, he noted.

“We adjusted for air pollution and diesel exhaust and we did find that there is an attenuation of the relationship, which suggests at least in a preliminary fashion that some of these relationships may also be explained by relationships or disparities in environmental exposures,” he said. “We call it ‘environmental racism.’ “

One of the areas the researchers are working on now is to identify within redlined vs non-redlined neighborhoods how various factors interact with each other, including air pollution, environmental urban design, soil/environmental toxicity and, importantly, gun violence, Al-Kindi said.

“I think there’s a neighborhood effect to a certain degree,” he said. “That neighborhood effect could be a combination of all of the above and needs further study as a marker of cardiovascular disease, both for prediction but also to identify gaps so we can address them.”

Although the 2021 MESA analysis suggested that living in historically redlined neighborhoods was associated with cardiovascular health only among Blacks, data was not available to model differences between racial and ethnic minorities, Al-Kindi said.

Other limitations include self-reported health outcomes in the PLACES database; unmeasured confounders such as behavioral and genetic factors; and the fact that the definition of redlining census tract boundaries has not been standardized across studies.

Commenting for theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology, Keith B. Churchill, MD, president of Yale New Haven Hospital, New Haven, Connecticut, said he’d like a deeper dive into the differential data between the Southern and Northeastern states and why cholesterol moved in the opposite direction of other cardiometabolic risk factors. But the overall data, he said, aren’t surprising.

“It’s probably more of a confirmation than a surprise,” he said. “But I agree with their conclusion that there is a real need for a microanalysis within these particular areas and populations around the access to care, issues around healthy foods, overall household worth, the economics that persistently drive this, and the overall environment in the area, and then thinking about solutions to those particular issues.”

Given the scope of the problem, Churchill said it will take not only a significant amount of time and intellectual expertise to really unravel the issues and think about solutions, but that the financial impact of actually bringing solutions to the table is going to be significant.

“I think, importantly, it really speaks to being very aggressive in our acknowledgement of the issues around social determinants of health and gender and its impact on our overall health and cardiometabolic health,” Churchill said. “And, doing what we can on an individual basis to not only identify but also work on steps from a clinical standpoint, from a medical standpoint, and from an environmental standpoint. [These are areas] that we have some control over [in our ongoing efforts] to improve the overall health and well-being of the patients and populations that we serve.”

The authors and Churchill report no relevant financial relationships.

J Am Coll Cardiol. Published online July 4, 2022. Abstract

Follow Patrice Wendling on Twitter: @pwendl For more from theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology, follow us on Twitter and Facebook .

Source: Read Full Article