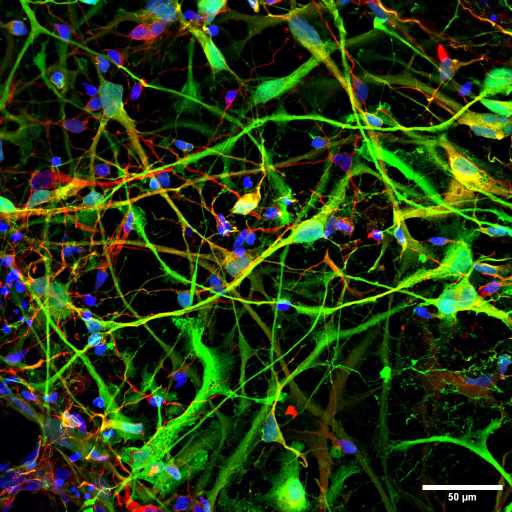

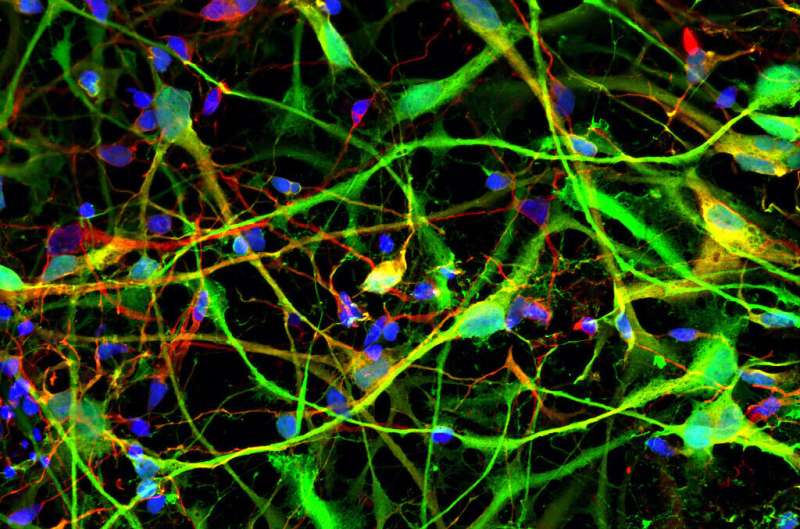

Researchers at North Carolina State University have demonstrated that neuron-like cells derived from human stem cells can serve as a model for studying changes in the nervous system associated with addiction. The work sheds light on the effect of dopamine on gene activity in neurons, and offers a blueprint for related research moving forward.

“It is extremely difficult to study how addiction changes the brain at a cellular level in humans—nobody wants to experiment on somebody’s brain,” says Albert Keung, corresponding author of the study and an assistant professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering at NC State. “What we’ve done here demonstrates that we can gain a deep understanding of those cellular responses using neuron-like cells derived from human stem cells.”

At issue is how cells in our nervous system respond to drugs that are associated with substance abuse and addiction. Our bodies produce a neurotransmitter called dopamine. It’s associated with feelings, such as pleasure, that are related to motivation and reward. When neuronal cells in the brain’s “reward pathway” are exposed to dopamine, the cells activate a specific suite of genes, triggering the feelings of reward that can make people feel good. Many drugs—from alcohol and nicotine to opioids and cocaine—cause the body to produce higher levels of dopamine.

“In experiments using rodents, researchers have shown that when relevant neuronal cells are exposed to high levels of dopamine for an extended period of time, they become desensitized—meaning the cells’ gene activation is less pronounced in response to the dopamine,” Keung says. “This is called gene desensitization. However, until now, it hasn’t been possible to do an experimental study using human neuronal cells.”

“Our work here is the first experimental study to demonstrate gene desensitization in human neuronal cells, specifically in response to dopamine,” says Ryan Tam, first author of the study and a Ph.D. student at NC State. “We don’t have to infer that it is happening in human cells; we can show that it is happening in human cells.”

In their study, Tam and Keung exposed neuron-like cells derived from human stem cells to varying levels of dopamine for varying periods of time. The researchers found that when cells were exposed to high levels of dopamine for an extended period of time, the relevant “reward” genes became significantly less responsive.

“This is an interesting finding, but it’s also a proof of concept study,” Tam says. “We’ve demonstrated that gene desensitization to dopamine occurs in human cells, but there is still a lot we don’t know about the nature of the relationship between dopamine and gene desensitization.

“For example, could higher levels of dopamine cause desensitization at shorter time scales? Or could lower levels of dopamine cause desensitization at longer time scales? Are there threshold levels, or is there some sort of linear relationship? How might the presence of other neurotransmitters or bioactive chemicals affect these responses?”

“Those are good questions, which future research could address,” says Keung. “And we’ve demonstrated that these neuron-like cells derived from human stem cells are a good model for conducting that research.”

Source: Read Full Article