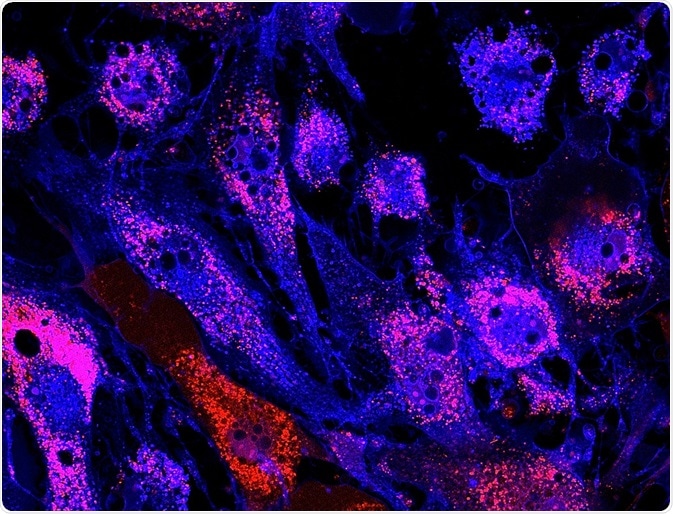

Stem cells are found in many different organs in the body, functioning to replace and replenish damaged or aging tissues. These cells have the unique ability to develop into many different types of cell and the ability to replenish themselves by continually dividing.

Credit: Vshivkova/Shutterstock.com

Stem cells differentiate to produce highly specialized cells, including brain and blood cells, and are vital to the maintenance of healthy organs. There are several different types of stem cell used in research: adult stem cells, embryonic stem cells, cloned embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells.

Adult stem cells

Adult stem cells are located in numerous sites throughout the body, functioning to maintain and repair tissues. These cells are multipotent, meaning they can develop into several types of cell.

The first work on adult stem cells was in the 1950s, researching the use of bone marrow stem cells in therapy. It was suggested that replacing diminished stem cell stores could prevent the associated damaging effects and be used to treat many different conditions. Hematopoietic stem cells are also used as a form of adult stem cell therapy, used in the treatment of autoimmune diseases, such as multiple sclerosis.

Corneal disease is also targeted with adult stem cells. In this case, a sheet of stem cells is placed over the eye, replacing the damaged stem cell stores. This method has been shown to treat blindness and has very good success rate due to the immune privilege of the cornea, which means they are can withstand the presence of antigens without producing an inflammatory immune response.

Oral mucosal stem cells have also been used to treat this condition, inducing them to transdifferentiate into corneal epithelial cells, allowing the patient to use autologous cells to prevent an immune response.

Embryonic stem cells

There are many different ethical issues with using embryonic stem cells, so much so that embryonic stem cell studies are very rarely published.

Embryonic stem cells come from the unused cells in IVF treatment. These cells are pluripotent, meaning they can develop into any type of cell, and therefore have great potential use in both understanding and treating diseases.

One paper that has been published so far is on the treatment of Dry Type Macular Degeneration. There is currently no treatment for this condition, which is due to the death of retinal epithelial cells and the build-up of proteins. These cells usually function to maintain healthy photoreceptors, therefore replacing the retinal epithelial cells could prevent the death of photoreceptors.

However, there are many different ethical concerns with the use of this technology as many consider an embryo as a living soul and therefore it is unlikely that these cells will be used in treatment. Embryonic stem cells are also not autologous to the patient and therefore the immunological response needs to be overcome.

Cloned embryonic stem cells

The original plan with cloned embryonic stem cells was that you could produce autologous stem cells which could produce any type of cell, thereby dismissing any immunological issues with using embryonic stem cells.

Cloned embryonic stem cells are made by removing the nucleus of the stem cell and replacing it with the nucleus from a somatic cell from a patient.

However, this treatment option has lots of ethical concerns as these embryonic stem cells are purely developed to be killed in comparison to embryonic stem cells which are left over from IVF. It is also very expensive and has since been replaced by the possibility of induced pluripotent stem cells. These cells, however, have been recently researched for uses in human cloning and are used to clone animals such as prize cattle.

Induced pluripotent stem cells

Induced pluripotent cells are originally somatic cells, which are reprogrammed to become like embryonic stem cells. It has been identified that through the transfection of transcription factors Ocr3/4, Kif4 and c-Myc by retroviruses, somatic cells can be programmed to become like embryonic stem cells. They are similar in many ways and have been differentiated into many types of cell.

These cells are advantageous as they are autologous to the patient and don’t have the tricky ethical concerns previously mentioned. However, the use of retroviruses could be dangerous and no one totally knows what will happen when they are used, as there have been no human trials so far.

Conclusions and future perspectives

Adult stem cell therapies have a successful previous record and have been shown to treat several conditions. Embryonic stem cells have great potential, but the ethical and immunological issues need to be overcome.

Cloned embryonic stem cells have too many ethical concerns to be used in treatment, but show potential for human cloning. Finally, induced pluripotent stem cells also show optimistic potential for treatment of many different conditions, however they initially need to be assessed in human trials.

Sources:

- https://stemcells.nih.gov/info/basics/1.htm

- https://www.medicinenet.com/stem_cells/article.htm#what_are_stem_cells

- Nakamura, T., et al. (2006). The Use of Autologous Serum in the Development of Corneal and Oral Epithelial Equivalents in Patients with Stevens-Johnson Syndrome. Investigative Opthalmology & Visual Science, 47(3), p.909.

- Tachabana, M., et al. (2013). Human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) derived from somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT). Science-Business eXchange, 6(21).

- Schwartz, S., et al. (2015). Human embryonic stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelium in patients with age-related macular degeneration and Stargardt's macular dystrophy: follow-up of two open-label phase 1/2 studies. The Lancet, 385(9967), pp.509-516.

Last Updated: Apr 22, 2019

Written by

Hannah Simmons

Hannah is a medical and life sciences writer with a Master of Science (M.Sc.) degree from Lancaster University, UK. Before becoming a writer, Hannah's research focussed on the discovery of biomarkers for Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease. She also worked to further elucidate the biological pathways involved in these diseases. Outside of her work, Hannah enjoys swimming, taking her dog for a walk and travelling the world.

Source: Read Full Article