Researchers in Singapore have conducted a study showing active replication of a human coronavirus in bats that occurred without the viral spike protein binding to host cell receptors.

One key interaction required for coronaviruses to enter host cells is the binding of the viral spike protein to host receptors such as angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in the cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) or aminopeptidase N in the case of HCoV-229E.

Now, researchers from Duke-NUS Medical School and the Bioinformatics Institute have reported extensive mutations in the genome of HCoV-229E viruses that resulted in the loss of spike protein expression, without any loss in the ability to infect bat cells.

Martin Linster and colleagues say that to their knowledge, their study is the first to report active replication of a coronavirus without spike receptor binding being required.

A pre-print version of the research paper is available on the bioRxiv* server, while the article undergoes peer review.

More about coronaviruses and zoonotic spillover

Coronaviruses (CoVs) are members of the Coronaviridae family that can be divided into four genera: the alpha-, beta-, delta-, and gamma- coronaviruses.

There are four seasonal CoVs circulating globally – 229E, NL63, OC43 and HKU1 – that together account for up to 30% of upper respiratory tract infections in adults. To date, three coronaviruses have spilled over from animals to humans (zoonotic viruses), namely SARS-CoV, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS)-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2.

Based on genetic analyses, all seasonal and zoonotic CoVs have been found to have an ancestral origin in bats.

For CoVs to emerge in humans, they need to overcome the host-species barrier by balancing conserved and modulating genes while retaining infectivity, replication and spread.

One key interaction that is required for coronaviruses to infect host cells is the binding of the viral spike protein to host receptors.

It has been proposed that alphacoronaviruses have a higher propensity for zoonotic spillover than betacoronaviruses, based on their broader range of host bat species and more frequent jumps in viral strains between bat genera.

The spike protein gene is highly variable

The gene that encodes the spike protein, particularly its receptor-binding domain (RBD), is highly variable, with multiple insertions and deletions having been observed.

Variants containing spike deletions have been documented in fatal cases of MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 and these were attributed to escape from humoral (antibody) immunity.

While some bat sarbecoviruses can bind human ACE2, most cannot attach to this receptor due to variation or deletions within the spike RBD, thereby pointing to alternative receptors or cellular entry pathways.

What did the current study involve?

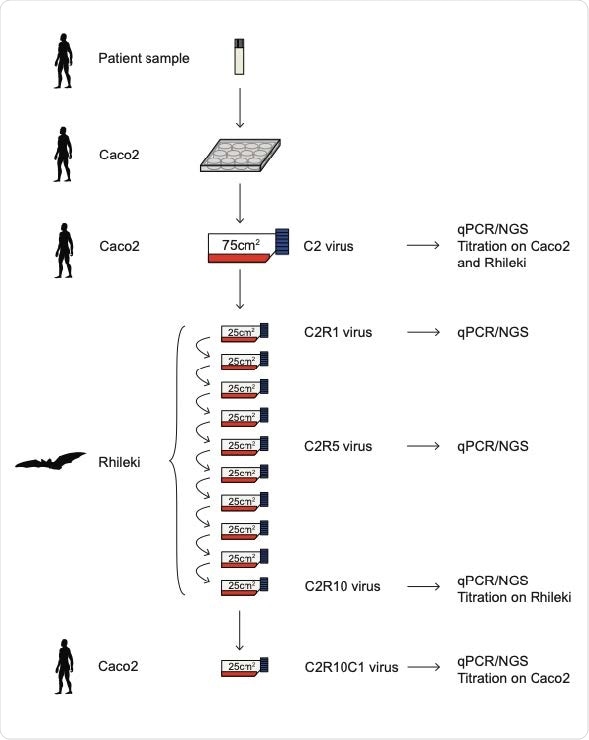

To help understand the adaptations required for coronaviruses to cross the species barrier, Linster and colleagues serially passaged six endemic HCoV-229E alphacoronaviruses in a newly established Rhinolophus (horseshoe bat) kidney cell line.

Stock viruses were derived from nasopharyngeal swabs and a reference strain passaged in human colon adenocarcinoma (Caco2) cells (denoted C2 viruses hereafter).

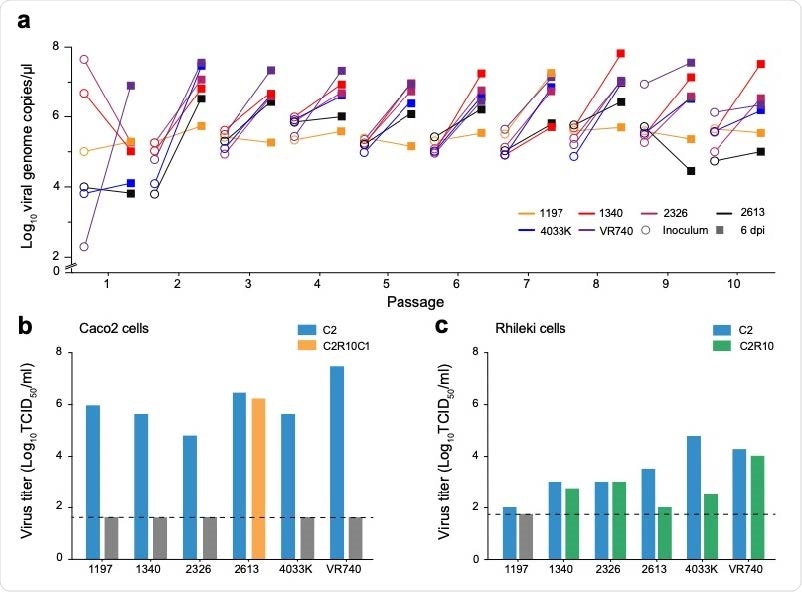

During virus passaging in Rhinolophus lepidus kidney (Rhileki) cells, the team observed an increase in viral genomic copies up to 6 days post-inoculation.

To determine the patterns of genomic changes that stem from the adaptation of 229E viruses to Rhileki cells, the team performed next-generation sequencing of full genomes recovered for Rhileki passage 1 (C2R1), passage 5 (C2R5) and passage 10 (C2R10) of the six viruses.

Remarkably, deletions of varying lengths were observed in the spike and open reading frame 4 (ORF4) as early as passage 1 in almost all of the Rhileki-passaged 229E isolates.

At passage 10, isolates SG/1197/2010, SG/1340/2010 and TZ/4033K/2017 exhibited major deletions in spike and ORF4, including deletion of the spike RBD.

The team suspects that large virus-containing vesicles may play a role

The researchers say that studies have recently provided insights into coronavirus replication, including the description of large virus-containing vesicles (LVCVs) containing intact or spike-less virions.

The team says this might help to explain the spike-independent virus maintenance in Rhileki cells observed in the current study.

Linster and colleagues say that given the wide range of hosts that alphacoronaviruses infect, the ability to replicate without the spike protein could provide an alternative route for infection between different bat species and possibly other hosts that may not share common receptors.

The team says that in this scenario, infection could be initiated by endocytosis of shed virions within LVCVs in urine or stool, and then be significantly increased through acquisition of a matching receptor-binding protein, either from recombination with the host or other coronaviruses.

“It is therefore critical that we gain a better understanding of the infection biology of host species, particularly the role of LVCVs, involved in the emergence of zoonotic coronaviruses,” concludes Linster and colleagues.

*Important Notice

bioRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

- Linster M, et al. Spike independent replication of human coronavirus in bat cells. bioRxiv, 2021. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.18.460924, https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.09.18.460924v1

Posted in: Medical Science News | Medical Research News | Disease/Infection News

Tags: ACE2, Adenocarcinoma, Angiotensin, Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2, Antibody, Bioinformatics, Cell, Cell Line, Coronavirus, Coronavirus Disease COVID-19, Enzyme, Gene, Genes, Genetic, Genome, Genomic, immunity, Kidney, Medical School, MERS-CoV, Protein, Protein Expression, Receptor, Research, Respiratory, Respiratory Tract Infections, SARS, SARS-CoV-2, Severe Acute Respiratory, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, Spike Protein, Syndrome, Virus

Written by

Sally Robertson

Sally first developed an interest in medical communications when she took on the role of Journal Development Editor for BioMed Central (BMC), after having graduated with a degree in biomedical science from Greenwich University.

Source: Read Full Article