More than two years into the COVID-19 pandemic, most Americans likely share the experience of anxiously awaiting the results of a COVID test, whether a lab-based PCR test administered at a hospital, a “point-of-care” rapid test given at an urgent care clinic, or an over-the-counter test taken at home.

Starting in spring 2020, as emergency rooms across the country began filling with patients with symptoms of COVID-19, many agreed to participate in clinical trials investigating the accuracy of COVID-19 diagnostic tests. The aim of such trials was to allow the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to quickly approve effective tests, which were in short supply yet necessary to help slow the virus’s spread.

The Department of Emergency Medicine at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis played a key role in investigating the accuracy of such tests administered in real-life conditions. Because the department has a strong infrastructure for conducting clinical trials, Washington University researchers, led by principal investigator Stacey L. House, MD, Ph.D., an assistant professor of emergency medicine, were in an ideal position to enroll large numbers of participants—more than 6,500—in these trials, compared with other emergency departments across the country. Many patients seen at the Charles F. Knight Emergency and Trauma Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital had the opportunity to participate in these trials.

“Our Emergency Care Research Center has a long history of conducting diagnostic and interventional clinical studies in the emergency setting,” said Opeolu M. Adeoye, MD, the BJC HealthCare Distinguished Professor of Emergency Medicine and head of the university’s Department of Emergency Medicine. “It is truly a unique resource that allows us to leverage our infrastructure to conduct scientific inquiries in a challenging clinical environment. Our experience and particular focus on emergency care research allowed us to play a pivotal role in the diagnostic studies of COVID-19. We were ready and believe we played an important part in tackling this pandemic. We’re especially thankful to all the participants who enrolled to help us evaluate the various tests, ensuring that only those deemed reliable would receive FDA approval.”

To date, Washington University’s emergency department has enrolled participants in 24 clinical trials evaluating COVID-19 diagnostic tests. Just over half of the trials were funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)—through its Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics (RADx) program—and the rest were funded by the companies that manufacture the tests.

“We are pleased that we were in a position to make important contributions to national diagnostic testing efforts during the pandemic,” said House, who is also director of research in the Department of Emergency Medicine. “Quite a few of the tests that we evaluated have gone on to be FDA-approved and are now on the market. And some of these were purchased by the federal government as part of the program to provide free tests to all Americans by mail.”

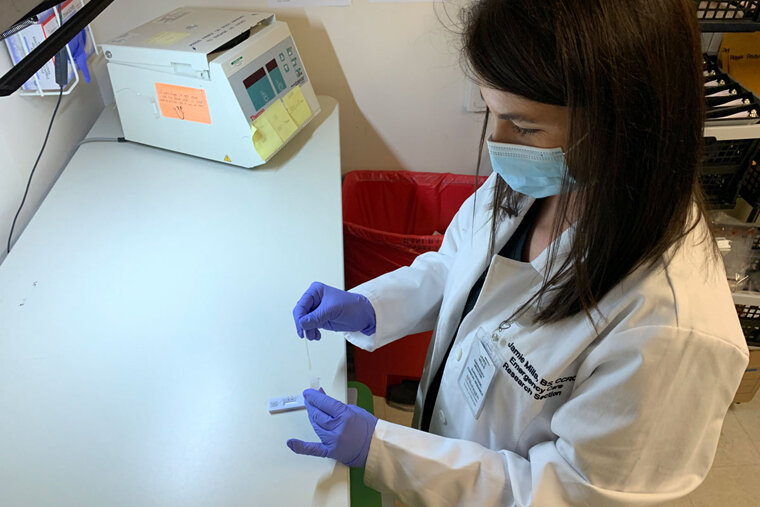

To be considered for approval, the point-of-care tests and over-the-counter tests being evaluated needed to show at least 80% agreement with the results of a lab-based PCR test, which is considered the gold standard for accurate COVID-19 diagnosis. As such, each study participant provided two samples at the same time—one for the investigational test, whether a point-of-care test conducted by a health-care worker or an over-the-counter test self-administered by the patient; and one for the gold-standard PCR test sent to a central lab.

In addition to investigating accuracy, House also led clinical trials seeking to determine the best methods of collecting patient samples—for example, comparing the use of nasal swabs versus nasopharyngeal swabs, the latter of which are capable of reaching deeper into a person’s nasal cavity; and the use of throat swabs versus saliva samples.

“There were a few studies comparing different types of nasal swabs—including the deep nasopharyngeal swabs that most people find uncomfortable and the shallow nasal swabs that only go into the tip of the nose on both sides—and the good news is that, if collected properly, the shallow nasal swabs work just as well,” House said. “That’s why all the home tests now use the shallow nasal swabs.”

For the approval of over-the-counter tests, patients must test themselves while a clinical researcher observes and makes notes on the process. To model the conditions of the average person testing oneself at home, the researcher is not allowed to help the patient in any way.

“Before we even began some of these trials, I sometimes had to tell the manufacturer that their test instructions were too complicated,” said House, also director of the Emergency Care Research Core. “They needed to simplify them before we could even get started—add pictures and diagrams, for example. We want these tests to be accessible to everyone, including people who don’t have any experience running these types of tests at home.”

During some of the trials, the researchers occasionally advised companies to redesign some of the equipment that came with test kits, House said. For example, patients couldn’t properly seal the sample in one type of test and ended up spilling the sample before it could be tested.

“We worked with companies to help them improve their tests, and we also had to be nimble and adjust to the rapidly changing course of the pandemic throughout these trials,” House said. “We have done these types of studies before, but never on this scale, never this quickly and never in situations where we had to change course because, for example, we couldn’t get the right type of swab for the test because of supply chain shortages.”

Source: Read Full Article