A new test that measures the quantity and quality of inactive HIV viruses in the genes of people living with HIV may eventually give researchers a better idea of what drugs work best at curing the disease.

Currently no cure exists for HIV and AIDS, but antiretroviral therapy drugs, or ARTs, effectively suppress the virus to undetectable levels.

Published today in Cell Reports Medicine, the study discusses how a new test, developed jointly by scientists at the University of Washington School of Medicine and Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, will give researchers, and eventually doctors, an easier way to gauge how much HIV virus might reside in a patient’s genome.

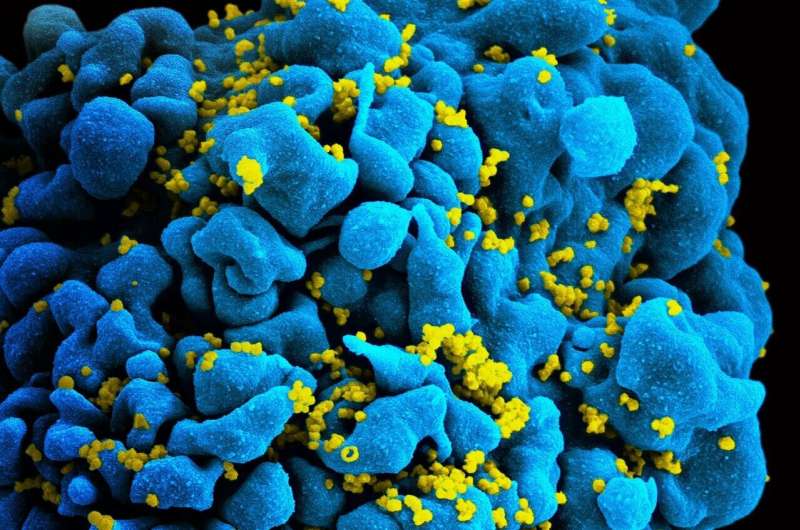

This latent HIV reservoir results from HIV’s integration into DNA, specifically in the chromosomes of T lymphocytes and macrophages, said Dr. Florian Hladik. He is the paper’s senior author and a UW research professor of obstetrics and gynecology. Viral integration into the host cell genome is a unique feature of retroviruses, he added.

Current tests are complicated, expensive, and sometimes give inaccurate readings of viral load, said Hladik. The two existing tests are done through sequencing the viral DNA from patient cells or inducing functional viral outgrowth in vitro from patient cell cultures. Both are time-consuming and expensive and do not lend themselves easily to the testing of new drug candidates to cure HIV.

“Our laboratory test is a simpler way to quantify the reservoir of intact viruses,” he said.

The evaluation of novel therapies to cure HIV infection relies on repeatedly measuring the number of cells that contain HIV DNA before, during and after treatment. Current assays do not give this information quickly enough or with enough accuracy to be useful in future clinical trials. And some of the assays require several blood draws from each patient-subject.

The test works by using a new type of assay that takes advantage of the multiplexing capacity of droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR). It probes each isolated DNA molecule not only for the presence of integrated HIV DNA, but also to determine whether the viral DNA is intact or defective. Commercial software and custom analyses are used calculate the number of T cells containing intact HIV DNA in the genome.

“This gives us a lot more information about the particular virus in a person’s body than previous PCR assays,” added Claire Levy, a UW research technologist in OB-GYN and the paper’s lead author. Previous assays, she said, were only partway effective—like searching for someone’s information online and learning only their first name. To continue that analogy, the new assay would yield more information, such as full name, age and height.

In the case of HIV, this extra information about the virus helps scientists understand how it is behaving in the human body.

Practically, this new PCR assay will help researchers determine the effectiveness of a drug candidate being tested against HIV/AIDS by closely tracking how many cells with intact HIV DNA exist after each dose, Levy and Hladik explained.

Source: Read Full Article